(Belated) St. Patrick's Day toast to America's Irish

My great grandmother immigrated to the United States from modern-day Serbia in the first decade of the 20th century. She was six- or seven-years-old at the time, and the story, as it was handed down to me, is that she traveled by boat (obviously) with only her older brother, who was just twelve or thirteen himself. Her brother carried a few letters from family in the United States and a set of handwritten instructions to help them find their relatives. This childhood ordeal alone must have been a greater adventure than most modern people will experience in their whole lives. My great grandmother lived an extraordinary life, scarcely imaginable to most people at a time when kids often aren’t allowed to wander down the block without adult supervision. Her life, though, was in fact quite ordinary for the time.

Research for the next Whose America episode has plunged me into the lives of 19th- and early 20th-century immigrant groups, and I thought that today we might talk a bit about the prototypical urban mass migration - namely, the mid-19th century Irish migration. It was an experience that permanently transformed American society and politics. Today, I’ve been fascinated by the shocking conditions these people had to endure and overcome to make their lives in America, so that’s what I’ll focus on here.

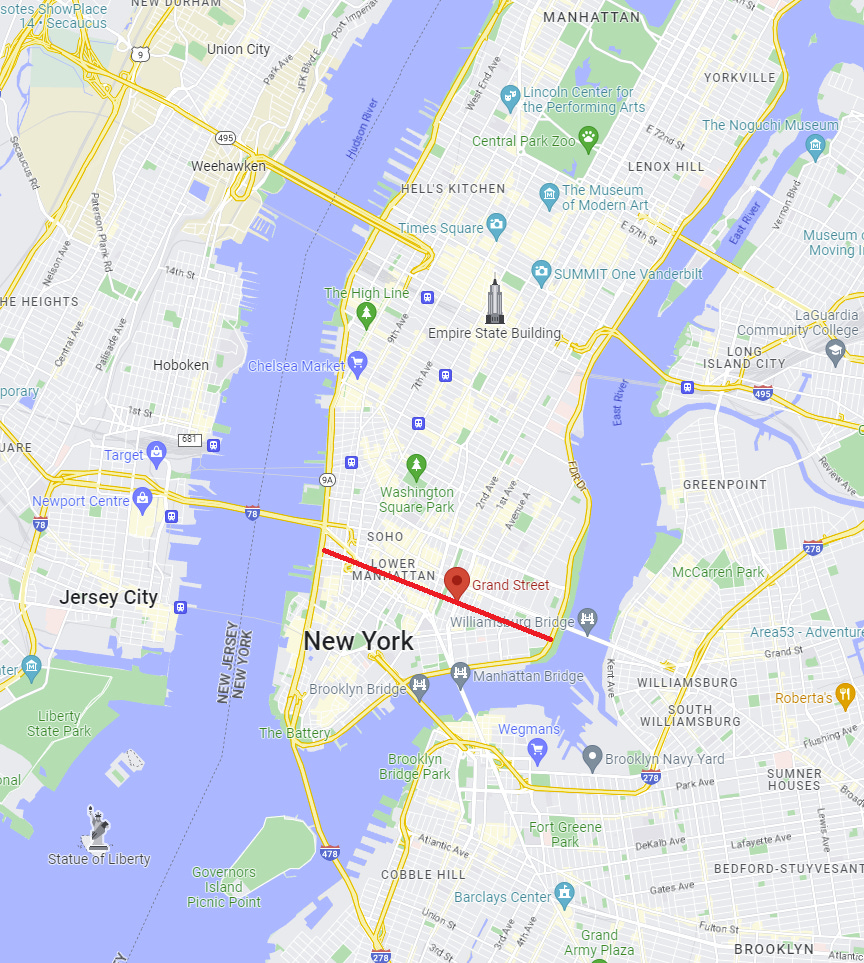

In the year 1800, there were only about 60,000 people in New York City. It took until 1820, two centuries after the founding of then-New Amsterdam, before the city had 100,000 inhabitants. A 60% increase in population in twenty years is a dramatic change, but at this time even most of Manhattan still consisted of farmland, and most of the population lived south of what is today Grand Street (the area beneath the red line on the map).

Beginning in 1825, the city would for couple decades add some 100,000 new inhabitants every ten years. By 1845, the population had exploded to 371,000. At the beginning of the century, New York City was primarily inhabited by Dutch and Anglo-Saxon families, with a smattering of French, German, and Irish residents as well. Old stock Irish immigrants to NYC, if they were not exactly prosperous, tended at least to have a skilled trade that allowed them to quickly make a life in the city (and no small number of them were actually prosperous). After the American Revolution, the prosperous immigrants were lost in an ocean of poor Irish leaving their homeland for what they hoped would be a better life in America. The Irish have always been fiercely independent, and before the 1840s most of those who arrived, though poor, were not necessarily desperate, but came to America for the promise of freedom from tyranny and to escape escalating sectarian violence back home. One Irish Catholic mother from County Wexford wrote in 1800 to her son in New York, “We remain here, but do not know how long it may be a place of residence, as the country is much disturbed by some unknown people who are rioting and burning every night. Our chapples are burning and tearing down.”

Previously, it had been difficult for the rural Irish poor to secure passage to America and still have enough money to help them survive until they were established here. But by the 1830s, enough Irishmen had immigrated that they began to make use of chain migration to bring their families along. Families pinched their pennies until they had enough to send one of their able-bodied young men to America. He would work as many jobs as he could find, and spend as little as he possibly could, until he had saved enough to send for another able-bodied young man from the family. The two would then combine their efforts, and this process was repeated until whole families and even communities were transferred to the United States. This allowed poor Irish for whom emigration would have been prohibitively expensive to make the trip, and by 1840 the majority of immigrants were impoverished, illiterate, often arriving without any urban skills except a capacity for work and a strong back.

The established Irish in New York City worried that the new arrivals would annoy the native population, and that their own reputations would suffer as a consequence. Several prosperous Irish businessmen set up an Irish Emigrant Society, an early forerunner of Jane Adams’s settlement houses, to help new immigrants adjust to life in their new country. As New York City became overcrowded with Irish immigrants, the men petitioned Congress to designate stretches of land in Illinois for exclusive Irish settlement, but that effort came to naught. Next, they created an Irish labor office to funnel new immigrants into canal-building and other construction jobs around the country to help them get started. The Society even distributed a guidebook for immigrants with helpful tips such as, “don’t drink very cold water when you are hot; don’t be tempted to drunkenness by cheap American alcohol; and don’t try to eat as much meat as the Americans.” (Anbinder, 2016)

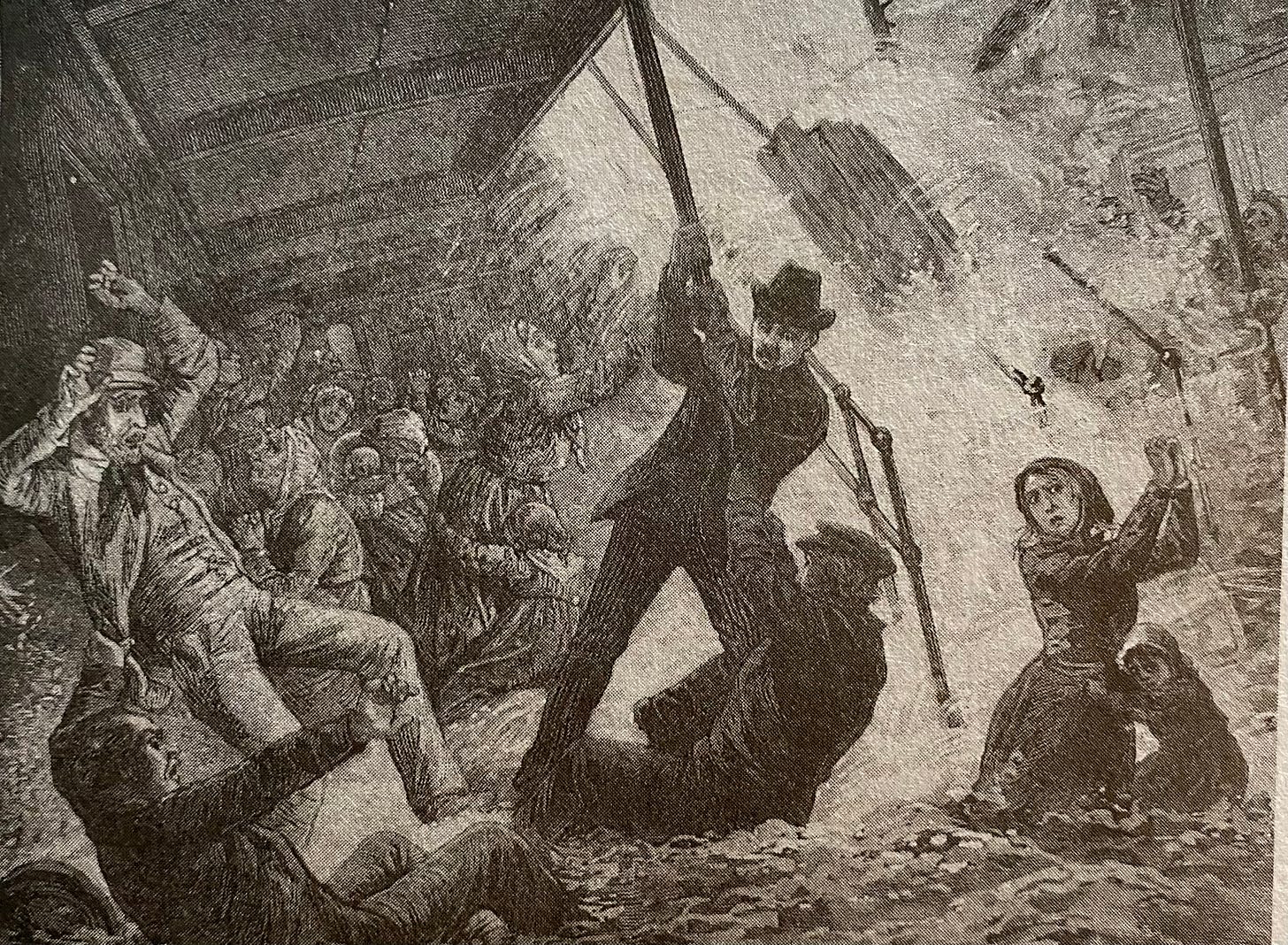

The poor Irish immigrants debarking in New York City were a sorry sight after enduring a brutal 4-8 weeks aboard a sailing ship to the New World. Those who were lucky had tickets in hand for a packet liner ship that ran on a predictable schedule. These were able to time their departure from Ireland to Liverpool (the port of departure for three out of four Irish immigrants) with more precision. The vast majority, however, were not so fortunate, and sometimes had to wait for weeks in Liverpool, using up their scarce funds or else sleeping and begging on the streets, for a space to open up for them. They tried to leave in the spring for the favorable weather, and because many would be arriving in America with hardly a penny to their name, and needed to arrive during the peak work season to quickly save up enough to get them through the first winter.

These poor immigrants couldn’t pay much for their passage, so ship captains made their profit by packing as many people as possible onboard. At first, the ships did not provide food for travelers, and even after Parliament passed a Passengers Act requiring provisions in 1803, most provided only meager amounts of stale or rotten bread, oatmeal, rice, or potatoes to ward off actual starvation.

Not only did the emigrants not get much food, but what they got was awful. The “ship bread” and “biscuit” were typically months old and rock hard. The voyagers needed to soak them in their precious ration of water to make them edible. Sometimes even that did not help. Often these foodstuffs became infested with maggots or otherwise spoiled. In 1848 on a ship headed for New York, Irish emigrant Henry Johnson received his weekly ration as two pounds of “meal” (probably cornmeal) and five pounds of “biscuit,” but the latter was so foul that even the pigs on the ship would not eat it. He had brought provisions from Ireland to supplement the ship’s allowance, but when he opened his trunk after a week at sea, he found it “alive with maggots and was obliged to throw it overboard.” He tried to beg food from others, “but it was every man for himself.” As a result, he recalled, “for the remainder of the passage I got a right good starving.” His voyage from Liverpool to New York took nearly eight weeks. (Anbinder, 2016)

Most poor Irish immigrants were only able to afford a spot in the ship’s steerage compartment two levels below the main deck. There were no windows in the steerage compartment, which was typically pitch-dark because the ship’s crew would not allow candles or lamps to be lit for fear of fire. The compartment was the same width as the ship itself, with bunks lining each bulkhead, one right next to the other with no space or dividers between them, for one hundred feet or more, with an identical top bunk running parallel. A one-hundred foot long berthing compartment often slept at least three hundred people, and most larger ships had two of these compartments, one forward and one aft. Adult passengers were allotted eighteen inches of bed space, with four people sleeping in each six-foot by six-foot bunk. Travelers often had to share beds with total strangers. There was no privacy, and if women wanted to change clothes or use the chamber pot, they had to do so in front of God and everyone.