Confrontation, pt. 1 - The Book of Job

During my recent discussion with Auron MacIntyre, a viewer tossed him a few bucks on SuperChat to ask about my views on the Book of Job. At various times in the past, I’ve mentioned that my views on the Job’s story are unorthodox (though not particularly original, except that my interpretation is a hodge podge of views I’ve gleaned from others). I told him it was too big of a question to address in a lighting-round Q&A, but that I would do my best to answer him here.

I suppose the first thing I should do is to beg the indulgence of my non-believing readers. You’re all interested in history and culture or you wouldn’t be here. Well, the Bible is the foundational document of Western civilization, and it informed and defined the lives of your ancestors for many generations until very recently. If you think there’s no God, that’s OK, just approach Him as a literary character, and this essay as a bit of literary criticism. Whether or not He’s up there sitting on a cloud presiding over a band of child harpists, that literary character has been the primary point of reference for most of our civilization’s history, and that’s a kind of reality, too.

To my Jewish readers: To avoid confusion among the portion of the audience less familiar with the Bible, I’m going to refer to the text as the Old Testament, rather than the Tanakh or the Hebrew Bible.

Finally: I will try to remember to use the term “Hebrew” to refer to the descendants of Jacob, but, if previous habits are any indication, I will probably use “Israelite” interchangeably here and there. If you see “Israelite,” it will refer to all of the twelve tribes unless otherwise indicated, not just the ten northern tribes of Samaria, but if I use the term “Jew,” it will refer specifically to the Kingdom of Judah - that is, the kingdom composed of the two southern tribes of Judah and Benjamin.

I recently completed a cover-to-cover reread of the whole Bible. It had been quite a few years since I’d done so, and I’ve thought, read, and experienced a lot that has shifted my perspective since the last time. One thing that did not change, however, is my conviction that the Book of Job is the hinge on which the entire story swings - or, certainly the Old Testament, at least. Job is the most morally difficult book in the entire Bible. It is frequently trotted out by non-believers to make a mockery of God, and it’s no wonder - the story of Job seems, at face value, to invalidate the simplistic claims about the character and purpose of God made throughout much of the rest of the Old Testament.

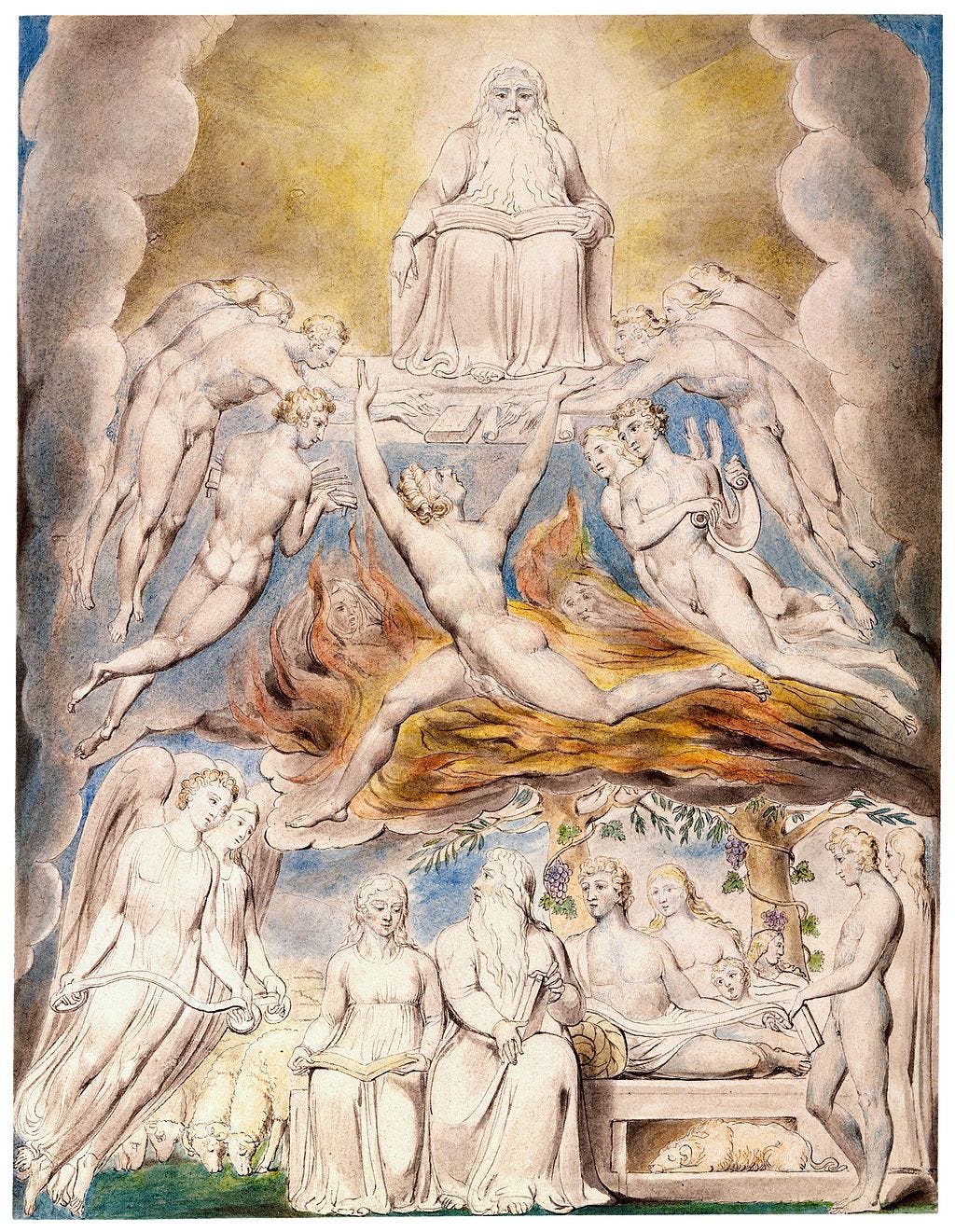

Most everyone will be familiar with the general outline of the story. God is holding court in heaven, and the heavenly beings are taking turns presenting themselves before the throne, in the manner of ministers making their reports to the king. One of them is Satan - actually, it is not capitalized here, and comes with the definite article attached, so it reads “the satan” (literally, “the adversary” or “the accuser”). So the satan presents himself before the Lord, and God calls him out, boasting of the man called Job, the most righteous and blameless servant of God on earth. Provoked, the satan says, sure, of course he’s righteous, you’ve given him everything. He’s rich, respected, healthy, and has a big family, why wouldn’t he sing your praises? (In the pop culture version of the story, it is often imagined that the adversary is the one who challenges God and provokes him to abandon Job, but in fact - and this is significant, I think - the devil was just passing through, and it was God who brought the whole thing up.)

God, of course, accepts the devil’s challenge, and tells him that he has free rein to do as he pleases to Job, though forbidding him to touch Job’s physical body. How to interpret this has been a subject of debate probably ever since the book’s author first started handing around the manuscript. God’s prohibition on the devil from physically harming Job indicates that God remains in control of the situation - that is, the devil may be inflicting the damage, but in so doing he’s acting as God’s agent. If God is, as most believers suppose, omnipotent (all-powerful) and omniscient (all-knowing), He can simply take a peek into the future to know how the game will play out, so what is He trying to prove, and to whom? Are we to believe that God cares what the devil thinks, that He cares about it so much that He’s willing to inflict torture on His most loyal servant just to change his mind? Or (and here perhaps we teeter on the edge of blasphemy) has the devil managed to introduce doubt into God’s own mind regarding Job’s fidelity?

For God to doubt would mean placing limits on his omniscience. There’s no room for doubt when you know. But the prologue of the Book of Job itself at least seems to imply that God might be subject to such limits, for when the devil makes his presentation, God asks him, “Where have you been?” Satan tells Him he has been “wandering to and fro about the earth, and traveling on it,” a fact which God ought to have known without asking. God then asks a follow-up question - “Have you seen my servant Job?” - which omniscience would have made unnecessary. Carl Jung, who naturally interprets the text in psychological terms, sees the adversary as the embodiment of God’s doubt, and the whole scene before the Heavenly Throne as an argument God is having with Himself.

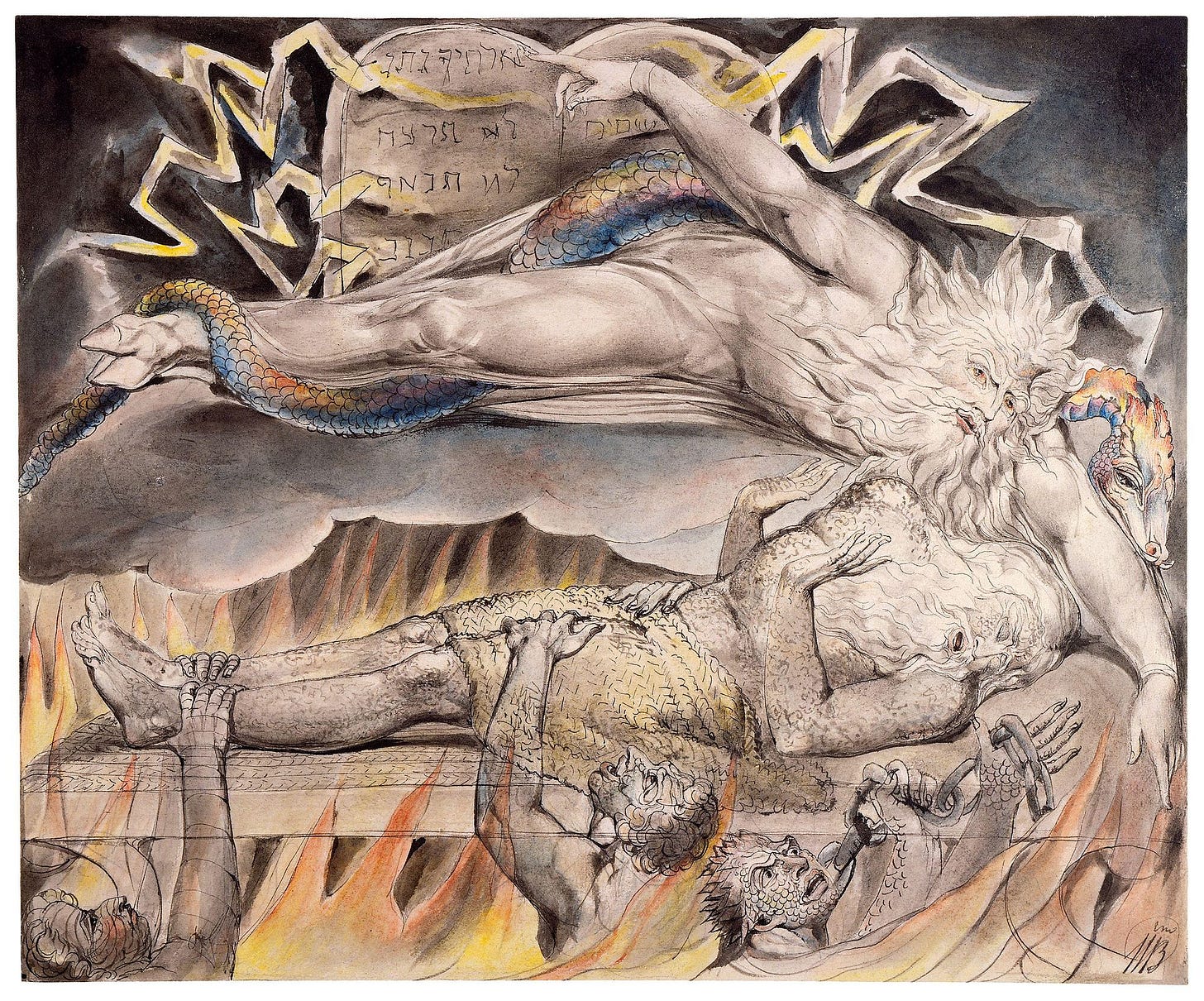

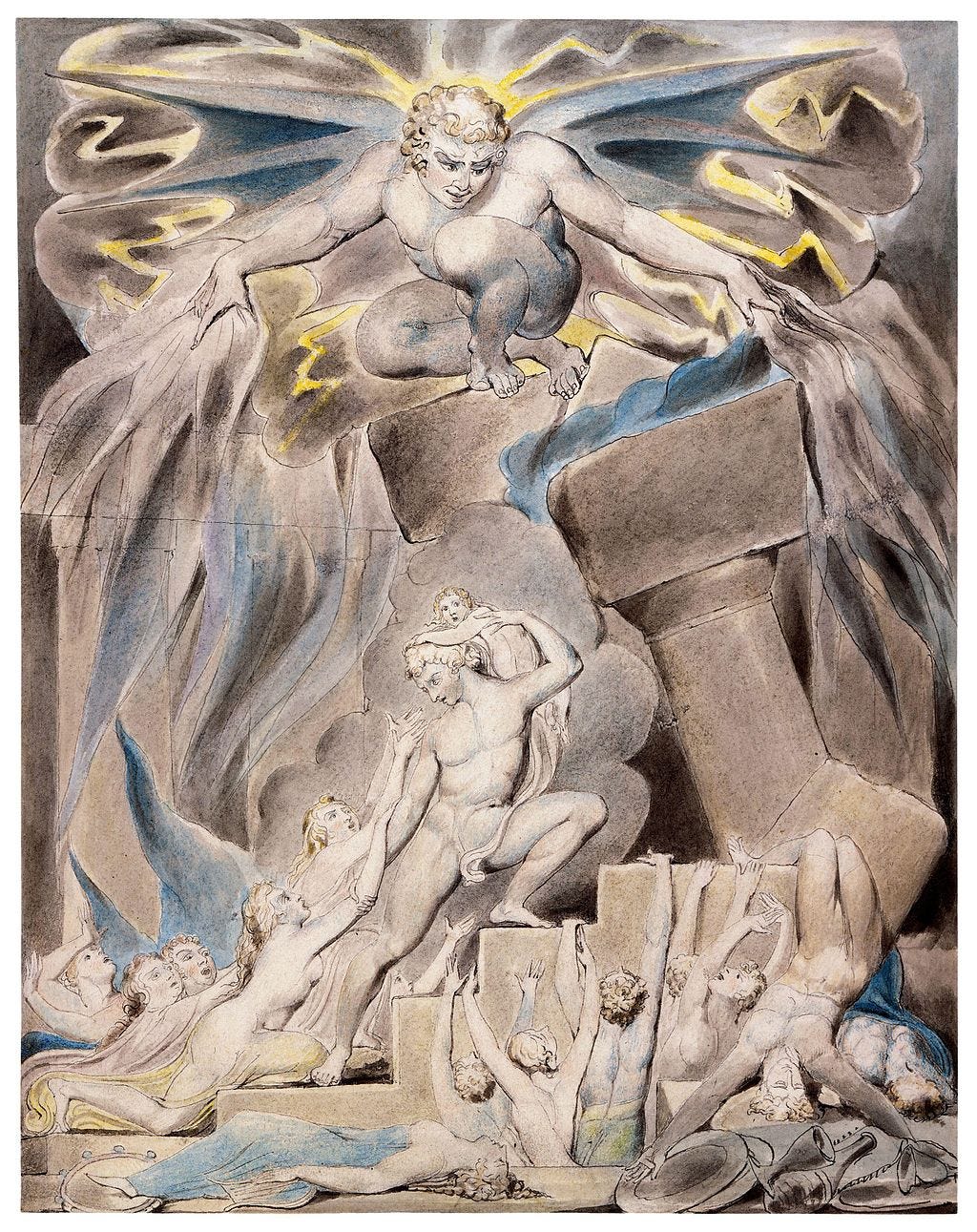

In any case, the devil goes ham on poor Job. That same day, many of his children were sharing a meal in the tent of their eldest brother when they were set upon by raiders, who killed all of Job’s sons and carried off his daughters into slavery. Lest Job be confused about the provenance of this assault, even as the messenger was delivering the bad news, another one ran up to tell him that lightning had come down from the sky and burned up more of his children, as well as all of his sheep. Then another: “Chaldeans attacked the camels and took them, and killed your boys, and only I escaped to tell you.” And before the third messenger had finished telling his story, a fourth rushed to tell Job that a great wind had collapsed the walls of house onto all of his remaining children. All of his wealth and possessions were destroyed or carried off, and every one of his children had been massacred, by the devil.

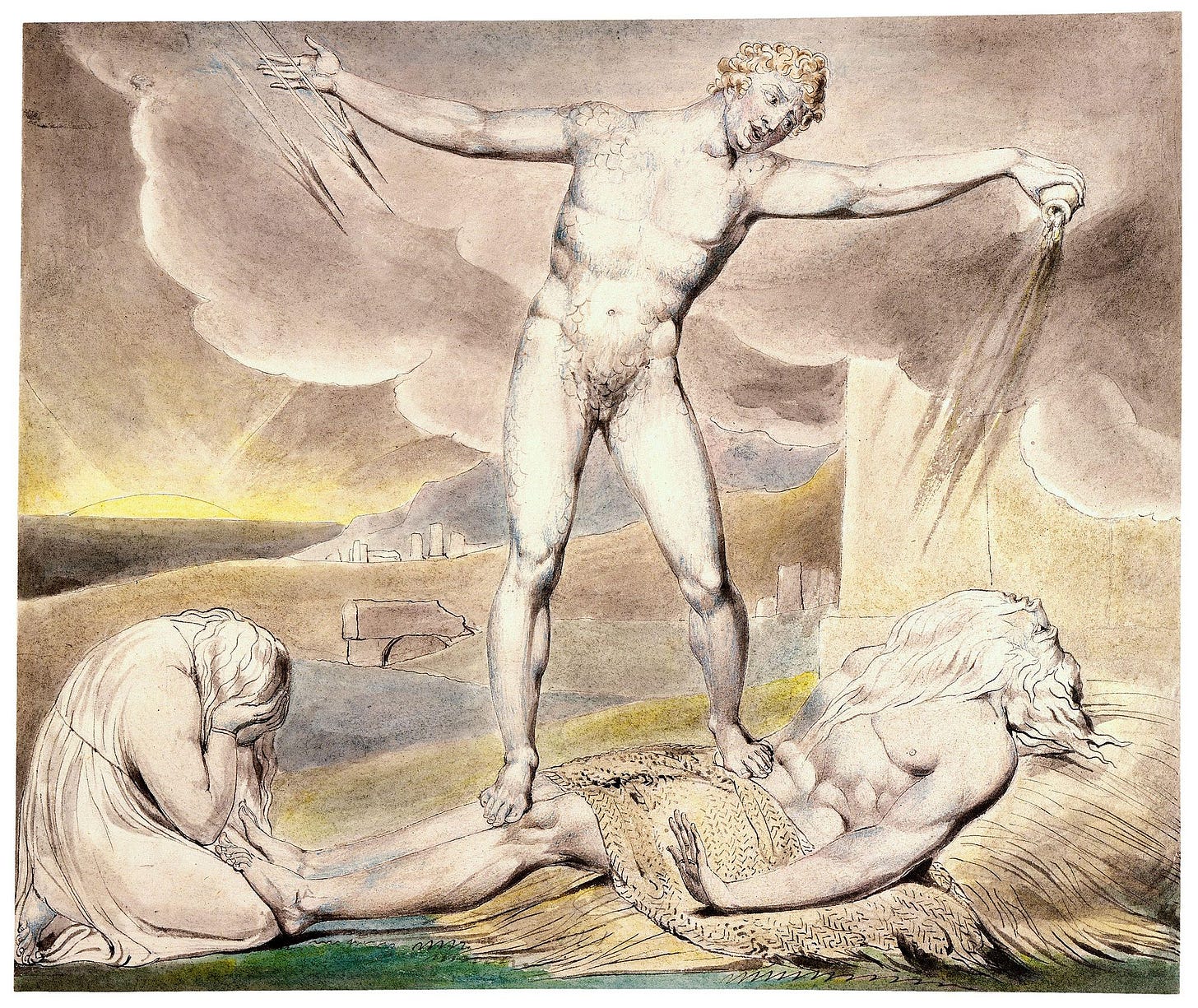

Job tore his robes and lay down with his face in the dust, and despite it all he blessed the Lord: “Naked I came from my mother’s womb, and naked will I return. The Lord gave, and the Lord has taken away; may the name of the Lord be blessed.” So far, “the patience of Job,” which gave rise to the well-known idiom, remained intact.

The scene cuts back to the heavenly throne room some time later, and the celestial ministers are once again making their reports to the Lord. As the devil approaches, God once again boasts of Job’s faithfulness, saying, “He has held fast to his innocence, even after you incited me to ruin him without cause.” Many Jewish and Christian apologists join Job’s friends, who will appear shortly, in insisting that, actually, Job must have done something to deserve his suffering, but God seems to reject their defense of Him. So the old devil says, so what? A man will give up everything he has to save his own skin. Give me power over his flesh and bones and he’ll surely curse you to your face. God says fine, do whatever you want to Job’s body, only stop short of actually killing him (reaffirming that God remains in control of the proceedings). Once again, the accuser seems to have manipulated God into attacking Job for no reason at all (as God Himself had just admitted).

The devil strikes Job’s flesh and blood, covering his whole body, from the top of his head to the soles of his feet, with painful boils. Bereft, Job sits down in the ashes of his ruined property, weeping bitterly and scratching his sores with a shard of broken pottery. His own wife comes to him and, speaking for the devil, says, “How long will you go on clinging to your innocence? Just curse God and die!” Although Job has been brought into disrepute by his misfortune - for this story takes place among people who believe, as Job always has, that righteousness is rewarded, and anyone suffering the fate of Job must have secretly been engaged in great evil - there are three friends who have not abandoned him, and they come to sit and weep with him over all that has happened. They weep together for seven days without speaking a word, and then, finally, Job opens his mouth:

God damn the day I was born

and the night that forced me from the womb…

Why couldn’t I have died

as they pulled me out of the dark?

Why were there knees to hold me,

breasts to keep me alive?

If only I had strangled or drowned

on my way to the bitter light.

Job has still not cursed God, but things are starting to get serious as this first part of the book comes to an end, and we find ourselves wondering with trepidation what he’s going to say next.

The story of Job is not original to the Bible, and is more likely a biblical spin on a tale long-known throughout the ancient Near East. A Sumerian and later Babylonian poem known alternatively as The Poem of the Righteous Sufferer or, if the title is translated literally, I Will Praise the Lord of Wisdom, have long drawn comparisons with the tale of Job, and, indeed, share enough characteristics that it’s fairly safe to assume that the Bible story was pollinated by these earlier versions. Scholars sometimes refer to the two works as The Sumerian Job, and The Babylonian Job, and both certainly predate the composition of the biblical story.

The earliest version of the Sumerian work dates from c. ~1700 BC, while the Babylonian version is more firmly dated to the reign of king Nazi-Maruttash (c. 1307-1282 BC) of the Kassites, who seized the remains of the Old Babylonian Empire after the Hittite sack of Babylon (c. 1531 BC). The original version records the lament of Tabu-utul-Bel, a prosperous official in the city of Nippur, and the later Babylonian version centers on a wealthy public official named Shubshi-meshre-Shakkan. In each version, the man is brought low and lodges a complaint against the injustice of his suffering. To Marduk, the king of the gods of Babylon, the poet sings:

From the day Bel punished me,

And the hero Marduk was angry with me,

My god rejected me, he disappeared,

My goddess left, she departed from my side…

The sufferer laments that the king’s courtiers have plotted against him, causing him to lose favor with the king and with it all of his possessions. He became a byword, an object of mockery and scorn, his days filled with terror and humiliation. The word around town was that, obviously, his apparent righteousness was all a ruse, and that he must have been living secretly in sin for the gods to have so abandoned him.

When I walked through the street, fingers were pointed at me,

When I entered the palace, eyes would squint at me in disapproval.

My city glared at me as an enemy,

My country was hostile to me as if it were foreign.

My brother became a stranger,

My friend became an enemy and a demon.

My comrade would denounce me furiously,

My colleague dirtied his weapon for bloodshed.

My best friend would slander me,

My slave openly cursed me in the assembly.

My slave girl defamed me before the crowd,

When an acquaintance saw me, he hid.

My family rejected me as their own flesh and blood.

It goes on like this for a while. Finally, his torment is multiplied by an affliction of painful and debilitating diseases. On the second of the four tablets, the sufferer mounts a feeble defense of his own conduct, saying that his god had treated him as one who lived unrighteously and failed to fulfill his religious duties, but that, in fact, “I was… attentive to prayers and supplications. Prayer was my common sense, sacrifice my rule.”

Finally, he is visited in dreams by envoys of the gods, who praise him for never cursing his lord, and then, on the god’s behalf, remove his afflictions and restore his place of honor, and that’s how the poem ends.

An Akkadian poem known as the Dialogue Between a Man and His God is the earliest known theodicy (a Greek term coined by Leibniz that refers to religious attempts to reconcile God’s justice with the problem of evil), composed a few centuries before the Babylonian Poem of the Righteous Sufferer. The Dialogue is shorter and simpler, but carries the same tune: a prosperous man brought low by painful illness and the collapse of his social position cries out for justice, and is finally restored by the renewed attention of his god, who praises his servant’s fealty in suffering.

Now, these ancient texts are relatively recent discoveries (c. mid-19th century for the Sumerian version), so it’s possible that some elements of the translation were influenced by the translators’ Judeo-Christian perspective. Other scholars, of course, have independently translated the poems in the years since, but later translators of ancient texts often begin with the accepted original version as a starting point and avoid venturing out with novel interpretations of basic themes and plot points. As a result, problematic translations can often survive the scrutiny of many eyes for a long time (as may be true of a critical passage in the Book of Job). Still, even allowing for that possibility, the similarities are too stark to ignore, and, given the well-documented cultural and demographic interpenetration of the peoples of the ancient Near East, and the much later composition date of the biblical story of Job (most scholars agree it is a product of the period of Babylonian captivity, c. ~597-538 BC), the baseline assumption should be that the stories are related to each other.

—-----------------------------

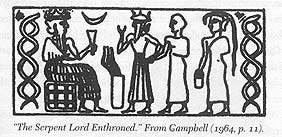

Such syncretism can be off-putting to more literal-minded Christians, who often balk at any suggestion that biblical stories might have been influenced by older, non-biblical sources. There are, for example, several Sumerian and Babylonian myths, all of which almost certainly predate the composition of the biblical Book of Genesis, that tell of a universal flood survived by only one man and his family, who had been warned to build a giant ship to ride it out. Tablets and seals from ancient Sumer, Babylon, Elam, and other places, depict scenes in which a woman is leading a male initiate to eat the fruit of a tree with a serpent coiled around it (or some variation on the theme, e.g., the fruit might be a drink, and the serpent might be a god wearing a serpent crown… but the similarities to Eve leading Adam to partake of the fruit she’d eaten at the serpent’s urging are hard to deny). Christians - and some Jews, although Jews often tend to be more flexible regarding the literalness of their own texts than many Christian sects - who insist that the Old Testament stories are historically factual do not approve of these comparisons, and find ways to argue around them, but when it comes to the Book of Job, at least, I don’t think that’s necessary.

One reason not to object to Job’s story being a common possession of the ancient Near East is written right there in the first verse of the book: “There was a man in the land of Uz whose name was Job.” The best guess at the location of the land of Uz puts it in the northwest corner of Arabia, near the Gulf of Aqaba - that is, not in the Hebrew heartland, because Job was not a Hebrew. This is far from the only time in the Old Testament that Yahweh takes an interest in the fate of a Gentile. Abraham - or, actually, he is still named Abram, since the scene depicted in Genesis 14 takes place before the covenant grants him his better-known name of Abraham - pays homage to Melchizedek, king of Salem and “priest of the Most High.” The verses that follow make clear that “the Most High” is not a generic title for some other god, but is Yahweh, the god of the Israelites. God commanded Jonah to prophecy against Ninevah, capital city of the heathen Assyrians, in order that they might repent and turn their hearts to God, which they do. King David’s mother was a Moabite. There are many such cases, which, to a Christian, prefigure God’s later expansion of the covenant to “all the nations.”

If Job is not an Israelite (and the rabbinical consensus is that he is not), then he was not subject to the Law. In fact, neither the law nor the history of the Israelites is mentioned in the Book of Job, and there is no indication that Job is a convert to the Hebrew religion. There is no reason to think he has ever heard of the Torah, or anyone named Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, or Moses. This, again, is not without precedent in the Bible. The fact that Melchizedek is called a “priest of the Most High” even though neither the Covenant nor the Law had been handed down when he makes his appearance is evidence that these things are not necessary prerequisites to being in God’s service (for Gentiles, at least). The Ninevites did not demonstrate the sincerity of their repentance by circumcising themselves or adopting the prohibitions and sacrifices of the Law, and it would have made no sense for them to do so because those things were required only of the Israelites as a sign of the special task for which they’d been designated.

If Job was not under the Law, then, what was his religion? Bible scholar Jack Miles calls it the Covenant of Eden: Job held to the same “religion” (so to speak) as the pre-Abrahamic patriarchs and Melchizedek, that is, he believed in one God who created the world, that God was good, and that one fulfilled one’s duties to Him by also being good.

Although it seems very likely that the Book of Job was a new twist on an old story told by their neighbors for a long time before the Jews wrote down their version, its uniqueness is not diminished for having been shared. None of the older versions even approach the Book of Job in the beauty of its verses, the depth of its theological ruminations, or the grandeur and ambition of its vision. The book is divided broadly into three parts. The first part was described above, beginning with God’s wager with the devil and ending with Job seated in silent suffering with his three friends. The second part is by far the longest, taking up most of the book, and consists of Job’s laments, his disputations with his friends as they try to justify God’s behavior, and finally God’s appearance to speak on His own behalf. The third part describes Job’s restoration. It is probably significant that the first and third parts are composed in simple prose, while the long middle portion is composed in poetic verse, in a meter apparently unique to the Hebrew Bible. The implication, I think, is that the prologue and epilogue represent the portions of the story well-known to readers of its day, while the long middle portion is the unique Jewish contribution. It is as if the ancient author was saying, “(Part 1) OK, so you all know the story of the righteous man who was abandoned by God and fell on hard times, right? (Part 2) Well, once his life came apart, here’s what he had to say about it, and here is what God said back to him. (Part 3) Finally, you all know what happens: since he remained faithful he was restored to his former place of prosperity and honor, the end.” In other words, the Book of Job may have been an early example of fan fiction spun off from a well-known story - which, again, I don’t think diminishes it any more than the works of Aeschylus or Sophocles are diminished by their derivation from ancient Greek myths. Nowhere in the Old Testament do the authors insist that every word of it records a historical event, and the presence of books such as the Song of Songs indicates that the compilers were not shy about including works that used a literary device to express a profound truth.

—--------------------------------------------------

There is one important aspect of the Bible about which almost everyone disagrees with me, namely, that God changes over the course of the story. I’ll discuss this more later on, but for now a few words will suffice. To most Christians and Jews, God is infinite and perfect, and since perfection has nowhere to go but down, God cannot possibly change. Change would either imply that He was less than infinite or perfect before, or that He is now.