Confrontation, pt. 3 - The Book of Job

I’ve been struggling mightily with how to end this series without creating a bunch of new threads I’ll feel compelled to tie up before moving on. It’s already delayed me too long, so I’m just gonna start typing and see what we get.

I’ll start this essay by restating two thoughts I’ve covered earlier in the series, and which will serve as the basis for this final installment.

First, God changes over the course of the Bible, and second, the Book of Job is the pivot on which the rest of the Bible story turns. Or, taking the two thoughts together, the Book of Job is the critical turning point in the transformation of God in the Bible. God’s speech to Job, in fact, is the last time God speaks for Himself in the Hebrew Bible. It is worth revisiting some of the highlights of the story leading up to God’s final message to man.

One of the most striking things about the Old Testament is that God gradually withdraws His presence over the course of the story. The God of Genesis walks in the Garden of Eden, and speaks directly with Adam and Eve. One of my favorite little details is that, after the Fall, when poor Adam and Eve had covered their nakedness with leaves, God made them some clothes before throwing them out into the world. The Creator of the Universe probably caused the clothes to appear by snapping His figurative fingers, but I like to picture Him taking their measurements, making the cuts, and sitting down with His sewing needle. Either way, the God we find in the second book, Exodus, is not one who would condescend to making a human’s undergarments.

The next four books tell the story of Moses leading the Israelites out of Egypt to the Promised Land, but rather than eating and chatting with the people, as He had done with Abraham, God appears as a pillar of smoke and fire, and manifests as earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. He speaks only with Moses, and from this point on God will communicate with the Israelites only through designated prophets. Even King David, whom we’re told the Lord loved like a friend, had to consult the prophet Nathan to receive any word from God. The messages of the prophets become more abstract and mysterious, and the vast majority of the people do not see or hear of God directly. Finally, in the chronological last two books of the story - Ezra and Nehemiah - God is only a whispered rumor.

God’s last direct appearance to a human being in the Hebrew Bible comes in the climax to the Book of Job. After Job calls God to the carpet to account for Job’s suffering, God finally shows up. Job is taken up into a whirlwind and provided with one of the most spectacular visions found in any piece of religious literature ever written. The only scene I know that really compares is in the Hindu Baghavad Gita, when Krishna reveals his ultimate form to Arjuna. The Indian text is actually interesting to hold up next to the Book of Job. They address similar questions (adjusted for cultural differences between ancient Hebrews and Indians) and resolve them in a similar manner. The Baghavad Gita is the most famous section of a much larger work, the great epic known as the Mahabharata. Its setting is the field of battle just before the climactic confrontation between armies on two sides of a civil war. Its protagonist is Arjuna, a great warrior who is struggling with an apparent contradiction in his religious duties. On one hand, he is of the kshatriya class, a warrior, and he has a sacred duty to fulfill his obligation to fight. On the other hand, there are friends and relatives arrayed across the battlefield against him, and what of his obligations to them? Arjuna concludes that it must be a greater sin to kill his friends and family than to shirk the duties of his caste, and decides to lay down his bow and refuse to participate in the battle. His chariot driver - who, unbeknownst to Arjuna, is actually the god Krishna in human form - tries to convince him to fight using the arguments that would have been common answers to the conundrum in those days. Some scholars have suggested that the Baghavad Gita was added to the Mahabharata in order to provide a theological response to challenges raised by the spread of Buddhism. If true, this runs parallel to the suggestion of some Bible scholars that Job’s friends were making the standard pat arguments commonly provided for God’s apparent abandonment of the Jews during the Babylonian exile. Krishna’s arguments fail on Arjuna just as the justifications of Job’s friends failed to persuade Job, and, after the debates run their course and Arjuna remains unconvinced, Krishna reveals his true form and gives Arjuna an unforgettable divine vision. Arjuna sees both armies rushing into Krishna’s gaping mouths and being crushed like grapes, rivers of their blood running down Krishna’s chin. He is shown that human life is a flash in the pan, and that he need not be worried about killing his enemy because everyone, on both sides, has already been dead a thousand times, and will die a thousand times more, killed not by Arjuna, but by the god who devours all without discrimination. Whole universes blink in and out of existence in the time it takes Krishna to take a breath. In the end, Arjuna sees that the divine reality whose laws he was attempting to judge is far beyond his comprehension, and that the duty of a man is to follow his dharma by fulfilling the obligations of the caste into which he was born.

Like Arjuna, Job is given a glimpse of ultimate reality - blood-crazed war horses snorting and stomping as they lust for battle, lions tearing apart gazelles, ravens desperately searching for food as their young starve in the nest. A passage from a piece in the recent Passage Prize book captures it well (it’s a little overwrought - OK, it’s very overwrought, but I’m giving the author the benefit of the doubt and assuming that he intended it that way):

All health, beauty, intelligence, and social grace has been teased from a vast butcher’s yard of unbounded carnage, requiring incalculable eons of massacre to draw forth even the subtlest of advantages. This is not only a matter of the bloody grinding mills of selection, either, but also of the innumerable mutational abominations thrown up by the madness of chance, as it pursues its directionless path to some negligible preservable trait, and then — still further — of the unavowable horrors that ‘fitness’ (or sheer survival) itself predominantly entails. We are a minuscule sample of agonized matter, comprising genetic survival monsters, fished from a cosmic ocean of vile mutants, by a pitiless killing machine of infinite appetite. (This is still, perhaps, to put an irresponsibly positive spin on the story, but it should suffice for our purposes here.)

Man is condemned to live out his days in a charnel house, killing and consuming simply to survive until his own biomass is consumed and repurposed by nature. This was the way of the world for billions of years before humans opened their eyes and realized what was happening. We love and seek meaning - and not only do we have the capacity for these things, but we need them desperately, we wither away without them. And yet, we know we will watch everyone we love die, or they will watch us die. Every meaningful moment of our lives will be forgotten, and even the larger collective projects through which we try to steal a small piece of immortality will eventually pass away. Some of us have faith that the end of this world is not the end of everything, but few of us are blessed with a vision like Job or Arjuna, and so our faith always stops short of certainty (and even those who’ve managed to talk themselves into certainty would do well not to dwell on it too much).

Could the universe have been constructed in a manner that would have spared us all this? Job spends much of his air time insisting that, yes, it could and should have been made that way. This is a hubristic claim, and God lets Job know it in no uncertain terms. God’s speech to Job has been interpreted as a bullying display of raw power meant to intimidate Job into silence, but I don’t read it that way at all. After all, God Himself chastises Job’s friends for trying to justify His actions by invoking terms like justice and virtue. He says that they have spoken falsely of Him, while His servant Job was the one who had spoken truthfully. A universe without change is one which does not grow or evolve, but to creatures caught in the wheel of time, change is experienced as suffering. God can accomplish miracles, but His power is limited by logical contradiction. He cannot create a universe that grows and evolves, but does not change - not because He is too weak, but because it’s simply a contradiction in terms.

An inventor can build a robot to serve him, but not to love him. To be loved, he must have a child. But children are risky, much riskier than a robot. Children die of leukemia, they stick their fingers in electrical sockets, they can be obnoxious and disappointing, and, despite your best efforts, they often grow up to be very different than you would have made them, had you been designing a robot. Even if everything goes according to plan, your children will watch you die one day, and then they may go before God to say it isn’t fair, to shake their fists at the sky, demanding to know why He would make a world where such suffering was not only possible, but mandatory. And what could He say, except that it’s not personal, and if I could spare you all this, I would, but - and you’ll just have to take my word for this, because you’ll never understand - it has to be this way. This is very far from the moral platitudes offered by Job’s friends.

The fact that Job merited a response at all speaks to the nobility of his stand. All of the usual arguments for why bad things happen to good people were tried against him, and none of them stuck. If Job had accepted those justifications, and repented of his or his family’s imagined sins, God might never have taken notice of him. He would have been just another man who’d suffered tragedy, his cry stifled by worldly rationalizations before ever making it to God’s ear. Just by showing up to answer the charges against Him, God was admitting that Job had a valid point. In my reading of the Bible, the Book of Job represents the turning point in God’s relationship with man because Job's firm stand forced God to recognize just what it was his human creations were going through. God had never watched a parent or a child die, He had never lost a spouse or become paralyzed from the waist down. He had never known hunger or thirst or desire or fear. When Moses led the Israelites out of Egypt, the people soon found themselves hounded by enemies and on the brink of starvation. In their distress, some of them spoke out of fear, questioning whether they had made the right decision, and God, who had never known fear, never known the terror of seeing one’s children shriveled from hunger, slaughtered them for it. He had no idea what they were going through, because He’d never experienced anything like it, and He slaughtered them for it. Job forced God for the first time to reckon with what His creatures were going through, with how the world looked and felt from the inside.

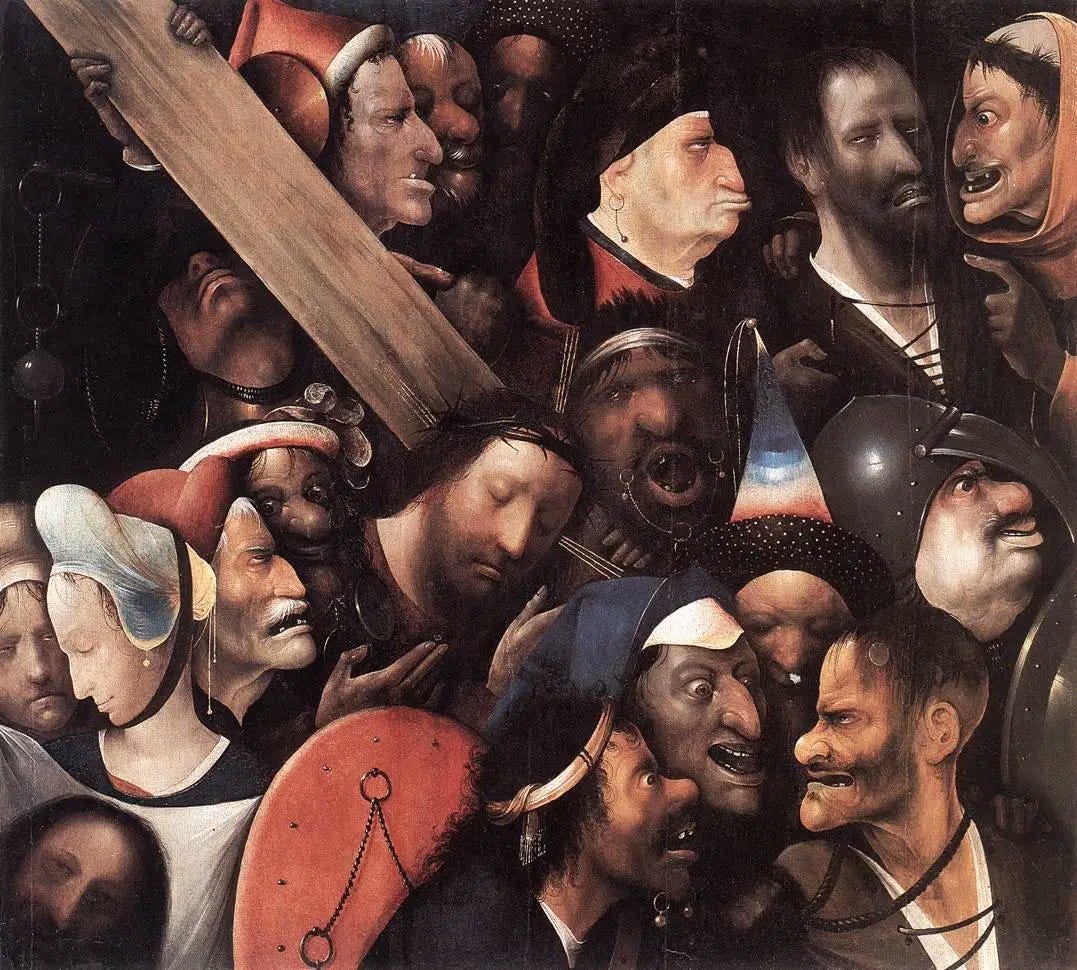

Yet the fact remained that the universe could have been created no other way, so what could God do to reconcile Himself to mankind? Well, I’m a Christian, so you know my answer. He couldn’t spare us the suffering without reducing us to machines, but He could come down to experience it with us. He was humiliated, tortured, and publicly executed, knowing in the depth of His being what Job and the rest of mankind had felt when they cried out, “Father! Father! Where are you? Why have you forsaken me?” The traditional Anselmian view of the Crucifixion sees Jesus as a blood sacrifice that reconciled man to God; that is, similar to the sacrifices of goats and rams, except one with the power to render all future sacrifices unnecessary. I won’t argue with orthodoxy, but that view has never sat well with me. The Crucifixion, in my view, reconciles God to man, allowing Him to say truthfully, “I understand how you feel, I finally understand, and I’m sorry it has to be this way, but I promise you everything is going to be OK.”

…

Ha. I’m getting a bit emotional writing about this, so I’m going to cut it off a little shorter than I intended. I’m getting soft in my old age.

Apologies for the low output lately. I’ve got a lot of pressing personal matters piled up, and been a bit stressed as a result. I’ve gotten into the habit of always writing 10-15 page essays, and I’m going to try to change that going forward. I like writing the long essays, and I will continue to do it, but the truth is, sometimes you have a 10 or 15 page essay in you, and sometimes you don’t, and I twist myself in knots when I don’t. But I’ve always got a page or two in me, so I’m going to try to focus on getting out shorter, more frequent work to you guys.

I can’t tell you guys how many times I publish something thinking, “OK, this is the one, they’re definitely going to hate it, probably cancel their subscriptions, I wonder if I could get my old job back…” and every time you all pick me right back up. I really appreciate it.

Darryl, you're deeply appreciated.