Murder, Mayhem & CIA Acid Parties

Let's give a bunch of criminals acid and see what happens

The other day, I happened across the trailer for Alex Lee Moyer’s upcoming documentary about Alex Jones, and it occurred to me that her previous film, TFW No GF, had been on my list for going on two years now. I watched it the other day, and it stirred up some sediment, so I’m currently working on a piece about some of the film’s themes. It’s a bit of a diversion, but only a bit. We’ve lately been discussing different modes of catastrophic human breakdown under modern conditions, and Moyers’s documentary is certainly no diversion from that.

It will be a day or two - or three, you know me - before it’s done. Some of my reading material for the episode, all of which are recommended to the curious:

A Phenomenology of Working Class Experience, by Simon J. Charlesworth - One of my favorites and I push it on everyone I can. Charlesworth, a sociologist, immerses himself in the lives of poor and working class people in post-industrial Rotherham, England. It’s not an easy read - the author draws heavily on philosophers like Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, and Badiou, and includes literal transcriptions of the broken English of subject interviews - but it’s a very rewarding one.

Stigma: Notes on Management of Spoiled Identity, by Erving Goffman - Goffman is another sociologist, and this book explores and describes how stigma functions in society and in interpersonal relationships. Stigma is a Greek term referring to some bodily mark or other sign which is supposed to expose something bad or unusual about the moral or social status of an individual. Slaves, criminals, and traitors, for example, would be cut or branded to advertise their status to all who met them. Today the meaning of the term has been broadened to refer to anyone with any distinguishing characteristic - a hunchback, facial burns, a physical handicap, a record of spending time in prison or a mental institution, etc - that consistently mediates between the individual and the rest of the world. Goffman is concerned with how stigma operates in a society, how stigma defines identity boundaries for both the ‘normal’ and the stigmatized, ways the stigmatized cope with their condition, the ways both the stigmatized and the ‘normal’ attempt to navigate the awkwardness of their encounters. It’s a short book, but very rich and gets to the point.

The Burnout Society, by Byung-Chul Han - Han is a Korean-German contemporary philosopher with insight into how technology and the structure of the economy are changing our society and ourselves. Han is not an easy writer, and there are times after re-reading his more obscure passages for the third or fourth time that I suspect he’s making a simple or nonsensical point, but this is the third book of his that I’ve read and each of them has gems that make it worth the relatively short investment (this book is only 60 pages, including footnotes).

OK, so anyway…

…in the meantime I thought I’d share something interesting that a friend reminded me about today. In the recent subscribers-only episode on the Israeli-Arab conflict, I mentioned an episode when Israeli intelligence let one of their military psychologists go to work for months on a Palestinian prisoner with the goal of brainwashing him to assassinate Yasser Arafat. The attempt, according to the official account, failed and the idea was abandoned, but I’ve always thought it was unlikely that it was a one-off attempt, and that if it had worked they wouldn’t have told us.

I don’t know much else about Israeli military intelligence programs of this sort, but I do know something about MK Ultra and related programs run by the CIA from the 1950s through the 1970s. The CIA destroyed most of the records on MK Ultra in order to prevent it from being exposed during the 1970s hearings on the agency’s illegal and unethical behavior, but over the years enough pieces have shaken out to reveal the outlines of a secret program that purported to use drugs, hypnosis, sensory bombardment & deprivation, and other techniques to attempt to manipulate, control and, sometimes, destroy the minds of experimental subjects.

In 1953, the CIA purchased massive quantities of LSD from Sandoz Laboratories in Switzerland, and immediately began testing its effects on subjects. The drug was administered, without consent, to mental patients, prisoners, military servicemembers, prostitutes and johns - “people who could not fight back,” as one agency officer put it. A mental patient in Kentucky was dosed with LSD every day for 174 days. Some test subjects went insane, others believed they had gone insane and committed suicide. The evidence suggests that the CIA was the first major importer of LSD into the United States. Although it was intended for experimental purposes, there are records of CIA employees taking it recreationally, and of CIA acid parties in the early days. According to one academic study: “Researchers were growing lax in controlling the drug. They began to share LSD in their homes with friends.” From there, the drug leaked into elite society, and then to the student population through students who volunteered for CIA-sponsored experiments. Novelist Ken Kesey, author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, was a participant in one of these early experiments while a student at Stanford in 1959. He enjoyed LSD so much that he took a job at the VA hospital where the experiments were being conducted so that he could gain access to the stash. After becoming rich and famous for writing his book, he threw wild parties for writers, poets, musicians and other cultural tastemakers, where he gave acid away like candy. In 1964, he and a bunch of his fellow heads took a psychedelic bus trip across the United States preaching the gospel of LSD. Soon, acid was everywhere and the counter-culture was on.

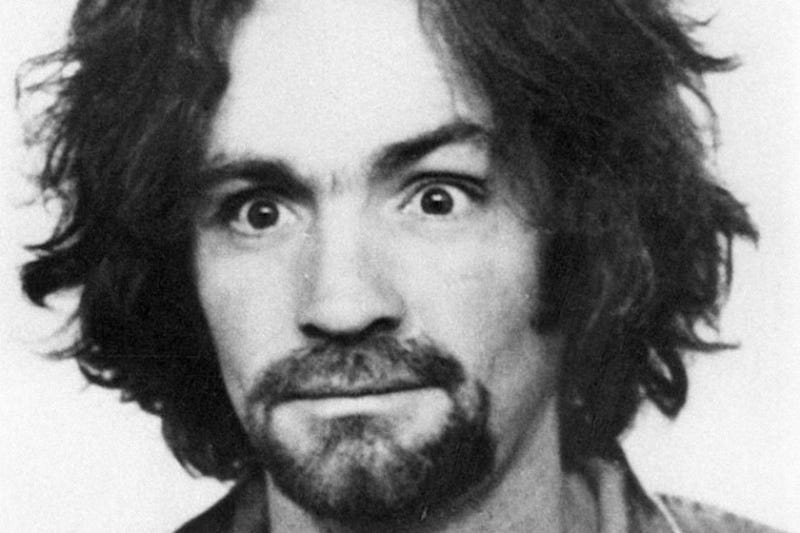

In the book Chaos: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties, author Tom O’Neil exposes gaping holes in the official story of the Manson Family murders. O’Neil himself is reluctant to put forward an alternative explanation, but he demolishes the mainstream Helter Skelter account, and provides strong circumstantial evidence that Charles Manson was the subject of a government-sponsored study of how various drugs and psychological techniques affected behavior, especially aggression, of individuals and groups. Manson’s parole officer, Roger Smith, was a postgraduate student studying criminology at UC Berkeley. It was Smith who advised Manson to move to Haight Ashbury in the summer of 1967, and it was then that Manson, previously a low-rent criminal on parole for forging checks, was first introduced to LSD. Smith was not a regular parole officer, and Manson was not a normal parolee. Manson was assigned to Smith under an experimental program called The San Francisco Project, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), a federal agency compelled by a judge in 1977 to admit that it had allowed itself to be used as a front for CIA operations. As the program required, Smith became much closer to Manson than was typical for a parole officer. Even within the project, Smith’s work with Manson was unique: The other six parole officers on The San Francisco Project were each assigned between 20-100 parolees each, but Smith only managed one: Charles Manson.