Notes on Immigration

Many of you heard my recent conversation about immigration policy, and a few of the comments afterward made me realize that I should have provided more context for the discussion. It started with an argument over a post I made on Twitter, and I know not all of you guys are on Twitter, so let’s do that now. There will be more to say about this in the future.

One of the difficulties of discussing immigration policy has to do with the question of scale. Imagine that you’re sitting in a room. The room is empty except for a desk with a chair, which you’re sitting in, facing the only door. Across from your desk is a family that wants to come to your country, and it’s your job to decide whether to let them in. They seem to be good, hard working people, with well-behaved children. Perhaps they’re refugees, or economic migrants, or just fleeing a corrupt and dangerous part of the world. They are not criminals, they are not carrying infectious diseases, they’re regular people looking to improve their lot and the lives of the children. What possible morally-satisfactory reason could there be for turning them down? Most people, I think, if they were sitting at the desk making the decision, would have trouble finding any justification that wouldn’t haunt them. I certainly would.

And so you pull out your big green APPROVED stamp, hand them their papers, and send them on their way. They thank you profusely, call down the blessings of their god onto you, and head for the door. When they open the door to leave, another family pushes in past them and is now standing before you on the other side of the desk. They, too, would like to immigrate. They, too, seem to be good, hard working people with well-behaved children, and are, for all intents and purposes, a carbon copy of the nice family that just left. But as the first family left the room and the new one shuffled in, you caught a glimpse of something outside the door and so you go to take a look. Outside the door is a line of people, stretching off to the horizon. You go up to the roof of the building and look out, but still can’t see the end of the line. An assistant gives you a note saying that each person has been given a number, and that so far they were up to 100 million. That’s the number of people estimated by the UN to have been forced out of their homes as refugees in the last decade. It doesn’t include people looking for work, escaping a corrupt government, or who simply want their children to live in the land of opportunity. Those people are showing up, too, and while you’re still trying to wrap your head around things another assistant comes with another note informing you that the line is now 120 million persons deep, and it’s growing all the time as people stream in from all over the world. At various places in the line, fights have broken out over rivalries of which you’ve never heard. Some of the fights have escalated into scaled battles between large groups whose tribes, ethnicities, or sects were at war in the place they came from. Another assistant comes, and it’s up to 150 million, with no end in sight. You go back into the room and sit at your desk, look up at the hopeful family and their glowing children, and let out a sigh. Now what? It will be just as hard to send that family away as it was before you knew what was outside the door. Maybe your heart can’t take it and you let them in. But a third family follows, and families keep following families into the room, and no matter how many you let in, your assistants keep coming with notes telling you that the line outside is only growing. No matter when you choose to cut them off, it’s going to be just as hard as it would’ve been to send the first family away - but you have to cut them off somewhere.

Since we changed our laws in 1965 to permit mass migrations from the Third World, we have added, by immigration alone, approximately the entire population of France to the United States. Every three months since Joe Biden has been in office, a number of people equal to the population of Seattle have entered the country illegally. This rate was briefly reduced in the last couple years of the Trump presidency, but otherwise it has continued that way, with ebbs and flows, at least since the early 1990s. The foreign-born percentage of the American population has reached levels not seen since the two great migrations of the 19th century, and almost certainly exceeds those examples when illegal immigrants are included in the number. Those mass migrations led to dangerous surges in nativism that not only pitted Americans against new immigrants, but Americans against Americans, just as the mass migrations of the last several decades have done today.

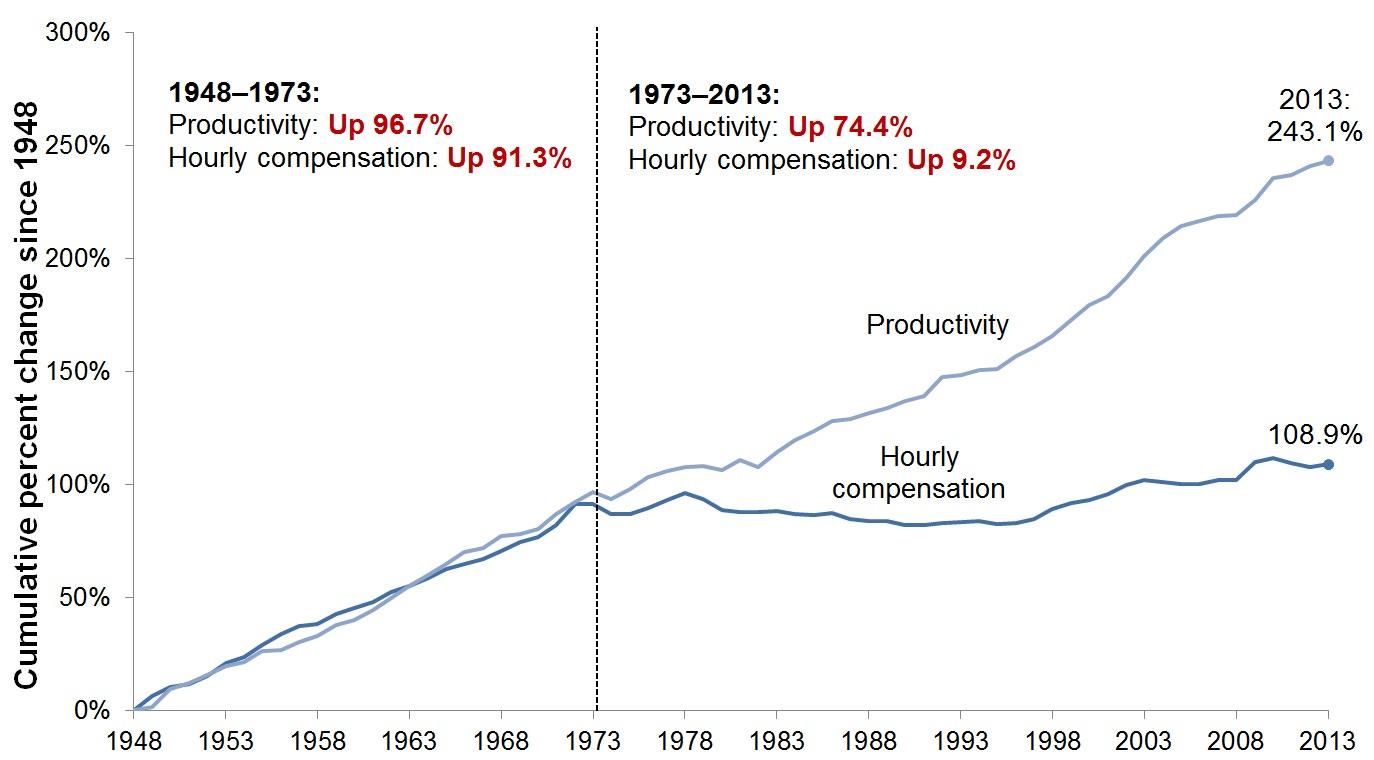

The situation in America has changed since the earlier mass migrations. From the country’s beginning until the 1970s - almost two hundred years - the United States suffered from a labor shortage. Immigrants who came to the United States, unless they arrived during one of our periodic depressions, would find work before they even left the docks, but even then industry was constantly starved for labor as workers left to settle the frontier or rush for gold. As a result, real wages (that is, wages adjusted for inflation) were much higher in the US than in Europe, and they maintained a strong upward trajectory for most of our history until about 1970. Since then, real wages have stagnated, hardly increasing at all for five decades, even as profits and productivity have exploded to the upside. The chart below shows that wages and productivity growth tracked together until the early ‘70s. The gap that has developed since then accounts for the surge in corporate profits over the last five decades - businesses have been getting much more out of their workers without having to meaningfully increase their wages. Much has been written about this, and I’m not going to try to adjudicate between the various explanations for the shift, but we can be sure that fifty years of stagnant wage growth is flashing a bright red signal that we do not need more workers.

American industry has been systematically shipped overseas for decades, as corporations scrambled to take advantage of developing countries that let them ignore American labor and environmental laws. Businesses that may have wanted to remain in the United States found they could not compete with others taking advantage of cheap Third World labor, and in the course of a few decades we outsourced 7.5 million manufacturing jobs. Of course, some jobs are location-dependent and so can’t be shipped overseas. An agricultural field is where it is. Same goes for hotels, restaurants, meatpacking, child care services, home care services, landscaping, car washes - exactly the jobs in which new immigrants, legal and illegal, tend to work. That’s the proper way to understand the economic aspect of mass immigration - it’s outsourcing for industries that are tied to a location.

It’s important to remember who exactly is being brought into competition with immigrant labor. It’s not me - so far, immigrants haven’t been starting up history podcasts (though, with the way things are going, AI may put me in a breadline sooner rather than later). They’re not competing with government workers or corporate bureaucrats. No, it’s the lowest end of the wage scale that is affected. It’s the poorest Americans - disproportionately black, Latino, and recently immigrated, by the way - who are being forced to compete for work with foreigners accustomed to a much lower standard of living, and whose customs have evolved to account for their poverty (for example, by having multiple generations of an extended family living under the same roof). Using illegal immigrant labor has all the benefits of employing parolees - one call is all it takes to send them back, so the workers have no recourse for poor working conditions, wage theft, or abuse by supervisors. If anyone complains, they can be replaced the same day with the next batch of new arrivals. It’s an employer's dream.

I could spend all day on the economics of mass immigration, but we need to move on. For now, just keep in mind that we live in a very, very different country than the one that took in millions of immigrants in the 19th and early 20th centuries. There is no more frontier to settle. Industry is not expanding, but contracting, and the information and service jobs that have taken its place do not require anywhere near the same amount of low- or moderately-skilled labor. In the past, a successful manufacturing business might employ whole towns or counties. Great businesses like Ford and General Motors supported the economy of whole regions. It’s not like that anymore. Facebook has a market cap of half a trillion dollars, and they could probably get by with 10,000-20,000 employees if they had to. The point is, we live in a very different country, with a very different economy, today than at any time in the past, and while the first generation of immigrants may come to plug holes in the lower end of the labor market, their children will be competing to move up a ladder that is pulled up further every day.

I regret not making the context of the discussion and the debate that preceded it known to everyone at the outset. The comment that set it off had to do with whether it was politically-feasible to halt mass immigration, deport the masses of undocumented immigrants, and reverse the demographic transformation of the country. I said that it was not feasible (actually, I said that the issue was “settled,” a poor word choice that led to some unnecessary confusion). Right wing Twitter took notice, and before long I was dodging incoming fire from a horde of angry frogs.

Our “debate,” then, had to do specifically with whether there was a realistic political path to stopping mass immigration to the US, and whether the approaching day when white people become a minority in America could be averted. Whether or not mass immigration should be stopped and what it would mean for white people to become a minority in America were not part of the debate since, for all of the people with whom I was arguing, it was a matter of common sense and ideological conviction that mass immigration should be stopped, and that white people becoming a minority would be bad. That’s why I opened the discussion by pointing out that white people are already a minority among kids 18 years old and under. Given that the average age of a white American (58) is more than double that of a racial/ethnic minority (27), the white share of the population will decline at an accelerated pace as the Boomers pass on. This means that, within a few years (the current estimate is 2045), whites will be a minority even if immigration is brought to a complete and permanent halt. The means that would likely be necessary to reverse that trend would be so draconian that even most immigration hawks would lose their stomach for it rather quickly - nevermind the overwhelming institutional resistance any such policy would face.

White demographic decline is obviously a touchy issue in this day and age, and I knew that I was stepping into dangerous waters when I brought it up. The subject is a perfect example of Michael Anton’s “celebration parallax,” which is summed up by the phrase, “It’s not happening, and it’s good that it is.” Liberal pundit Michelle Goldberg can write triumphantly in the New York Times that “We Can Replace Them,” but if the newspaper published a conservative op-ed with the headline, “They Are Replacing Us,” both the paper and the writer would immediately come under vicious attack. That’s the celebration parallax.

The reason I raised the issue - well, there were two reasons. First, at the risk of repeating myself, my debate partners were very concerned about the prospect of white demographic eclipse, and our discussion centered on whether it could be averted or whether, as I believe, the thing they’re worried about has already been accomplished. Second, white voters provide the overwhelming base of political support for hawkish immigration policies. Assuming that remains the case, a declining white population will continue to correlate with declining support for restricting immigration, so it’s very relevant to the question of whether such restriction is feasible.

The United States was 90% white until the 1970s. The truth is that we’re currently embarked on a novel experiment in multi-ethnic, multicultural democracy, and it’s still very much undecided how it’s going to turn out. Certainly recent trends have not been encouraging. Part of the problem is that Americans have been conditioned to read these questions in terms of the black civil rights movement, rather than in terms of previous waves of immigration in the 19th and early 20th centuries. During and after the mass migrations from Europe, it was expected that immigrants were coming to America to become Americans. Most immigrants embraced that, and those who didn’t were subject to social penalties and other forms of pressure. Even internal migrants were expected to conform to their new surroundings. My father’s side of the family were Okies who migrated to California to escape the Dust Bowl in the 1930s. The Okies were rowdy, impoverished, hard-drinking, uneducated rural Southerners, and let’s just say Californians did not exactly roll out the red carpet for them. Even after they graduated from their migrant tent cities to houses and apartments, the Okies and their descendants formed the core of the white underclass in California’s Central Valley. I grew up in that underclass, and I remember when I or my friends would misbehave, especially in ways that were sloppy, violent, or vulgar, our parents would often chastise us by saying, “Stop acting like a little Okie!” Our parents knew that we had to shed those markers if we were going to make it into the middle class, just as the Irish, Jewish, Polish, and other immigrants knew that their children had to assimilate in order to succeed.

This changed in the 1960s with the Great Migration of blacks out of the rural South into cities of the North and West. And it changed for understandable reasons. My mother telling me to stop acting like a little Okie hits differently than telling a misbehaving black kid to stop acting like a little Negro (not that it didn’t happen: I heard more than one parent of my black friends say it, often using a harsher word than Negro). James Baldwin spoke forcefully about the shame and stigma felt by his generation for their black skin, and as the ‘60s wore on, the black solidarity movement became more about asserting dignity and authenticity than political or economic demands. Middle class values and habits came to be seen as white values and habits, and assimilation was called a form of racial treason. This was a disastrous turn, since dignity can only be sustained if it is accompanied by success, and many were rejecting precisely the values and habits success requires. Unfortunately, we picked exactly this time (1965) to open the floodgates to Third World immigration, and many of the immigrants - or, more often, their children - took this view of assimilation as their own. Today, on the academic left and in the institutions under its influence, it is considered an irredeemable sin against political correctness to suggest that immigrants should compromise with American culture. Proponents of this perspective call up memories of Indian boarding schools and equate demands to assimilate with cultural genocide.

I try to approach these questions pragmatically, and not to pretend that America is a unique exception to the forces that have affected other countries in years past. It’s a common sense historical fact that massive demographic change leads to conflict, especially in the lower- and working-class communities who compete with the migrants for work and living space. I remember several years ago (I think it was 2006), there was a pro-immigration demonstration at Balboa Park here in San Diego. The radio said there were at least 50,000 demonstrators, so I drove to the park to take a look. It was a raucous demonstration, and dotted throughout the crowd I saw people carrying American flags hung upside down, or poles with Mexican flags flying over the American flag. I heard later that some American flags were burned. It is predictable, and perfectly normal, for Americans to react negatively to a scene like that, and, given that the immigration debate has been absorbed into America’s racial cold war, it is reasonable for white people to wonder how the emotions on display in that park will play out once the demonstrators achieve political dominance. I’m not saying it’s right or wrong, I’m saying it’s normal and predictable, and that we ignore it at our peril.

Political correctness demands that we treat group questions by the standards of individual charity. I worked for several years in Ventura County, California, and I drove to work through a landscape of strawberry fields, celery fields, you name it. And every day, no matter how early I went in, the Hispanic migrant workers were already there, bent over, picking fruit, and sprinting with their harvest back to the truck because they were paid for how much they picked, not for how long they worked. And every day when I’d drive home, no matter how late I left work, I’d drive back through those fields, and those people were still there, busting their asses. A lot of those people were illegal immigrants, and many of them lived in a few run-down trailer parks I’d pass on the way. I remember one morning, when I was driving into work, I passed the trailers as the kids were loading onto their school buses, and I’ll never forget the scene because there were about as many parents as there were kids out there. They were mostly moms, because dad was working the fields I’d just passed, and they were doing regular mom things like fixing collars, wiping off smudges of dirt, and kissing their kids. When the buses pulled away, the crowd of parents stood on the sidewalk and waved goodbye until their children were out of sight. It wasn’t the first day of school or anything like that, it was a regular Tuesday or Wednesday in the middle of the year. And then I realized that the parents had been out there the previous morning, and that they were actually out there every time I happened to drive by before the school buses left. These were good people, people I want in my country and my community. But immigration policy is not about individual people, it’s about populations. When we make the decision that it is immoral to deny any of them entry, we should keep in mind that behind them, on the other side of the door, is a line of deserving people stretching off to the horizon and growing all the time.

Obviously, this is a huge topic and I’ve barely scratched the surface, but I’m realizing that this is going to turn into a book unless I cut it off somewhere. If there are any specific aspects of this issue you’d like me to address, or any questions about how I’ve presented it, put them in the comments and I’ll do my best to answer. Thanks for reading.

Immigration lawyer here. I think one of the defining characteristics of this age is an inability to separate policy goals from personal moral sentiments. It’s gotten so bad that we end up relying for civil order just on the inertia of laws and policies made in the past. Take asylum law as an example. The definition of a “refugee” is very specific. It covers, for example, a fear of returning to your country because of persecution based on your political affiliation. However, most of our asylum applicants are fleeing gangs in Central America or are women from the same region fleeing domestic abuse. And the gangs are real, and they’re scary, and the domestic abuse is often horrific. But it doesn’t meet the current laws. And we lawyers and advocates and judges who are liberal-leaning can shake our heads and shrug and say, “What can you do? The law is the law. Damn that law.” But as far as I know, nobody has ever proposed changing it. If we did change it, basically every person in Mexico and Central America would qualify for asylum. And nobody seems to want that. Trump says out loud he doesn’t want it, to boos and jeers. Biden, to crickets, works out complicated deals where Mexico detains migrants on their side of the border where they then die in horrific fires. We’ve become profoundly dishonest with ourselves about what we want and what is good for us as a people. Nobody out there, at least in my community, is having any kind of rational discussion about what we want out of our asylum program, or what our goals are for our H1B program (which we use to import most of our engineers, doctors, and tech workers), who stands to benefit and who stands to lose. What are the implications for our democracy and sense of nationalism? How do we square that with our economic wants? Who do we want here? Skilled? Unskilled? Christian? Hindu? Very conservative Venezuelans? Very liberal Europeans? How do we balance labor with personal pity? Nobody is talking about it. And not talking is making us dumber. We’re like medieval peasants seeking shelter in a building made by some past civilization that we no longer know how to repair or engineer.

Excellent as always.

There's something that Americans who haven't had experience of living in a poor third-world country for at least a little bit of time do not understand: that poor people aren't a species, but a very diverse group who have very diverse viewpoints about themselves. When I lived in a South Asian country I came to understand that many extremely poor people had middle-class values and aspirations for themeslves, and many others didn't.

We should want, here, to accept for permanent immigration status those people whose values make them good candidates for successful assimilation because they have a strong sense of themselves as sharing *our* basic values, regardless of the specifics of their cultures.

But of course the second and subsequent generations may betray that expectation. But if you fail to even attempt to choose wisely, you will end up with a very bad result.