Stream of consciousness...

Nathan and a few others asked about the Third Worldist ideology that swept over the black rights movement in the 1960s. Specifically, he asked: “Do you consider Third Worldism to be connected to or the same as the exporting of Marxism from Western intellectuals to the former European colonies so that the oppressed peoples of the world could throw off the colonial masters?” I’m not sure I fully understand the question, but let’s use it as a prompt and see what falls out.

Today, the term “Third World” is often used as a blanket term to describe undeveloped countries. I’ve actually encountered a lot of Americans over the years who thought the number represented a ranking - the First World (US & Western allies) is at the top, the Third World (almost all postcolonial countries) is at the bottom, and even though nobody ever uses the term, they imagined a Second World in the middle (Mexico, Brazil, Soviet bloc countries, etc). The Third World is a concept that grew out of the Cold War, and it referred to smaller, weaker nations that did not want to subject themselves to the imperialism of either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The ideology of Third Worldism (a clunky term, and I wish there was a better one) is based on the idea that only by uniting and acting in concert could Third World peoples guarantee the non-interference of the great powers in their domestic affairs. This was manifested, for example, in the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), which, if I’m not mistaken, was initiated by Josip Broz Tito, the ruler of communist Yugoslavia, in cooperation with Nehru (India) and Nasser (Egypt).

One way to think about the Cold War is as a competition between the two big players for the loyalty of the global Left. Tremendous forces were unleashed in - you know what, let’s take a little detour.

Tremendous forces were unleashed in the 19th and early 20th centuries as Western countries went through a process familiar to anyone who’s studied the late Roman Republic. The Republic was founded and built to accommodate a citizenry made up of independent small landowners. During the period of Roman expansion, millions of captured slaves flowed back to Italy and drove down the cost of labor. Cheaper labor and tribute from the budding empire in turn drove down prices for agricultural products, until margins were so low that only gigantic latifundia employing armies of slaves could stay afloat. As large estates swallowed up the small ones, former freeholders flowed into Rome and other cities looking for work, and very quickly the Roman citizenry of small landowners was replaced by an urban mob. It soon became clear that the mob would be a decisive new force in Roman politics, capable of tearing the society apart, or of elevating to absolute power leaders who learned to give the mob what it wanted.

The rise of the urban public represents a definite break in the political history of any society. In the Roman Republic or feudal Europe, landholders were organically connected by blood and loyalty to others, and the political system was structured by this interlocking network of natural hierarchies. A landowner is a political actor almost by definition. He is a locus of all kinds of social and economic relationships fixed in place by a value system that privileges honor and loyalty up and down the hierarchy, and which, together, add up to something capable of organized political action. Social capital that had been built not over years, but over generations, quickly dissolved when people who had been independent farmers were reduced to mere employees and herded into multi-story urban tenements.

The great German philosopher of history, Oswald Spengler, wrote about this in his magnum opus, The Decline of the West. The changes I’m describing here coincide with the transition from what Spengler calls the Culture phase to the Civilization phase of a society:

The transition from Culture to Civilization was accomplished for the Classical [that is, the Greco-Roman -DC] world in the fourth, for the Western in the nineteenth century. From these periods onward the great intellectual decisions no longer take place all over the world, where not a hamlet is too small to be unimportant, but in three or four world-cities that have absorbed into themselves the whole content of History, while the old wide landscape of the Culture, become merely provincial, serves only to feed the cities with what remains of its higher mankind. World-city and province - the two basic ideas of every civilization - bring up a wholly new form-problem of History, the very problem that we are living through today with hardly the remotest conception of its immensity. In place of a world, there is a city, a point, in which the whole life of broad regions is collecting while the rest dries up. In place of a true-type people, born of and grown on the soil, there is a new sort of nomad, cohering unstably in fluid masses, the parasitical city dweller, without traditions, utterly matter-of-fact, without religion, clever, unfruitful, deeply contemptuous of the countryman and especially that highest form of countryman, the country gentleman. This is a very great stride towards the inorganic, towards the end - what does it signify?

The world-city means cosmopolitanism in place of “home”… To the world-city belongs not a folk, but a mob. Its uncomprehending hostility to all the traditions representative of the Culture (nobility, church, privileges, dynasties, convention in art and limits of knowledge in science), the keen and cold intelligence that confounds the slow wisdom of the peasant, the new-fashioned naturalism that in relation to all matters of sex and society goes back far to quite primitive instincts and conditions, the reappearance of the panem et circenses in the form of wage-disputes and sport stadia - all these things betoken the definitive closing down of the Culture and the opening of a quite new phase of human existence - anti-provincial, late, futureless, but quite inevitable.

Industrial machinery played the role of enslaved war captives in the modern version of this process. Powered machines allowed us to produce much more food using a fraction of the human labor. I have a vegetable garden in my backyard. It’s a fun hobby, but one of the things I was actually surprised to learn is that it is usually no more expensive to buy food from the store than to grow it myself. By the time I bought the equipment, garden soil, and fertilizer, paid the increased water bill, and built the raised beds, I’d be just as well off (financially speaking) if I went to a Super Wal-Mart instead - and that’s without putting any monetary value on the work we put into it. This is pretty remarkable when you consider that the veggies we get from the store were probably grown far, far away and the low price includes not only the transportation cost, but wages and salaries for everyone from the Guatemalan fruit pickers to the Wal-Mart corporate office. To a city-dweller, this is an almost unmitigated good; to a small farmer feeding a family and selling his excess yield to buy necessities he can’t make himself, it is the end of the world. Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, millions of families previously engaged in agriculture were driven from the countryside to look for work in the cities.

In a radio lecture on Hegel and Marx, the German political philosopher Carl Schmitt retrieved the early Hegel’s concept of the bourgeois as “the man who is essentially apolitical and in need of security.” The proletarian is also defined in essentially negative terms: “it is the class which does not receive a share of surplus value, has no home, no family, no social guarantees, and hence is nothing but a class, without any other community. It is a social nothingness whose mere existence refutes the society in which such a nothingness is possible.” Schmitt, of course, understands that very few (especially in his day) truly have no home and no family, but he’s pointing to the transient nature of modern life and the transactional nature of modern relationships. Someone who moves from Austin to Los Angeles for work, and may move again if the right opportunity arises, does not have a home in either place, even if he owns property in both cities.

By the early 1900s, it was becoming clear to many that this new urban mass would be the decisive political force of the 20th century. As Nietzsche foresaw, nationalism and socialism were both, in their way, attempts to make up some of the losses that resulted from these massive dislocations. After the First World War blew apart the empires of Central and Eastern Europe, the newly-formed nation states experienced political upheaval throughout the ‘20s and ‘30s. When the empires of France and Britain fell apart after the Second World War, there was a similar release of energy in their former colonies. Fascism and Bolshevism had shown the world how this newly-unleashed power could burn whole continents to the ground, and the Cold War - to return to the point that began this stream of consciousness - was in large part a competition between the US & USSR for influence and control over that power.

For example, consider the difficulty faced by US policymakers when competing with the USSR for the loyalty of a newly-independent African nation. The Soviets were able to make a very compelling case to African leaders by simply pointing out that black people weren’t allowed to drink from white water fountains in large swaths of the United States. This Cold War imperative was top of mind in the Eisenhower administration when it deployed the 101st Airborne to forcibly integrate Alabama schools in 1957. Privately, Eisenhower told Chief Justice Earl Warren that the Southerners fighting integration were “not bad people… All they are concerned about is to see that their sweet little girls are not required to sit in school alongside some big overgrown Negroes.” These personal feelings were put aside by a President who knew how badly Southern segregation was damaging our credibility with the Third World. It’s not a random coincidence that the West began to turn on apartheid South Africa at precisely the same time that the Civil Rights movement was picking up steam. Looking at it from the other direction, the US risked permanently alienating and radicalizing its black minority if America had a hostile relationship with newly-independent African nations. It was a powerful message that resonated outside of Africa, and fed communist propaganda insisting that the apparently-separate battlefields of the global revolution, from Algiers to Hanoi to Pyongyang to Birmingham, were actually all one battlefield in a global uprising of the world’s oppressed against white, racist, Christian imperialism. This became the predominant narrative by the 1960s, when it was clear that the Western working class was not interested in revolution.

(Proof-reading this, I am now certain that I did not answer your question, but I’m gonna move on. You’re welcome to clarify in the comments, Nathan, and I’ll be happy to pick up the thread.)

Here’s something that came to mind while I was answering that question. The expansion of the CIA’s mission to include shaping culture provides another view of the full spectrum of Cold War strategic considerations. For example, in the late 1960s and early ‘70s, the CIA funded and promoted the famous feminist author and activist, Gloria Steinem, and her feminist magazine (“Ms. Magazine). The agency may have done this to counteract Soviet propaganda regarding Western gender inequality, or to accelerate the splintering of the ‘60s protest movement into a thousand squabbling interest groups - probably both reasons played a role. The CIA also funded and promoted writers, editors, and artists, as well as literary journals and other high-culture publications.

The Agency didn’t invent the post-war literary movements that first spread through the pages of magazines like The Partisan Review and The Paris Review in the 1950s. But it funded, organized, and curated them, with the full knowledge of editors like Paris Review co-founder Peter Matthiessen, himself a CIA agent.

The Agency waged a cold culture war against international Communism using many of the people who might seem most sympathetic to it. Revealed in 1967 by former agent Tom Braden in the pages of the Saturday Evening Post, the strategy involved secretly diverting funds to what the Agency called “civil society” groups…

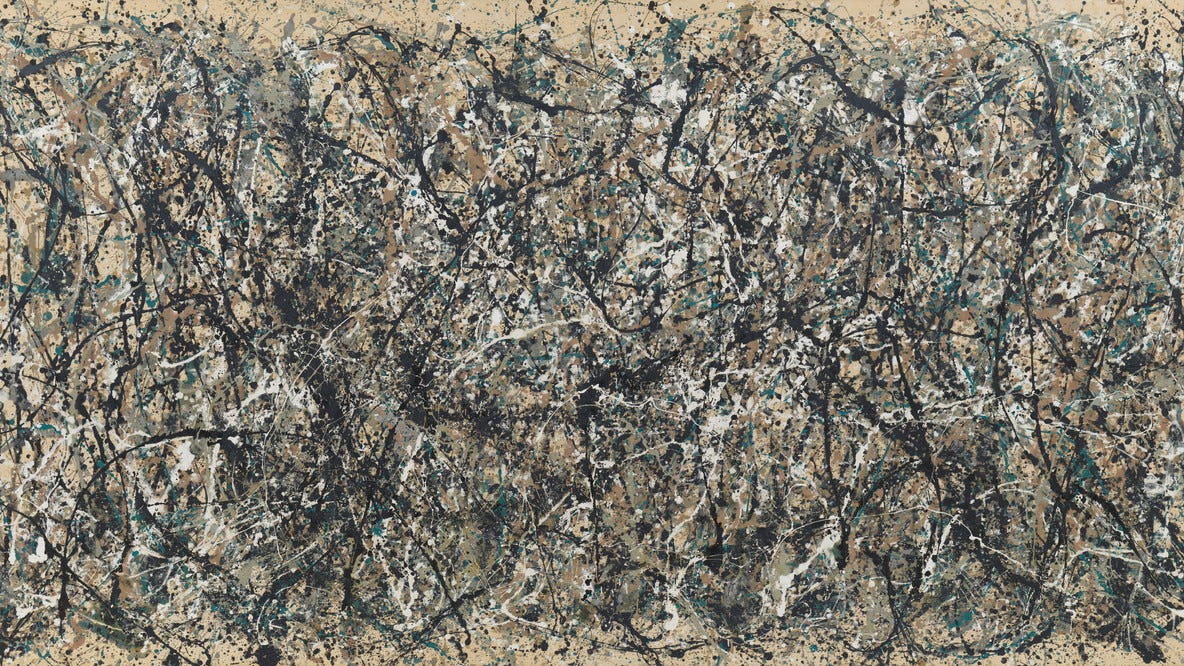

When, in 1965, the singer Louis Armstrong went behind the Iron Curtain as a “jazz ambassador,” and between performances he criticized racism in the United States. Armstrong’s tour, it turns out, was actually funded by the CIA. Perhaps most well-known is the CIA’s intervention in the modern art world, supporting painters like Jackson Pollock and other abstract expressionists. CIA fronts bought their paintings for exorbitant amounts to drive up interest, and ensured that they were displayed in the most prestigious venues. The agency used its influence over art and literary journals to promote their work. When this was revealed in the 1970s, the theory put forward in many art-world think pieces was that non-representational art was hard to use for communist propaganda, but it may have simply been that the CIA was manned exclusively by Ivy League men who liked to think of themselves as cultural tastemakers. Thomas Braden, the man in charge of the CIA’s cultural operations back then, had been the executive secretary of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City when that institution was leading the charge into abstract expressionism, and wrote his own account in 1967.

Abominable Sonoman asked about the claim raised in the Nation of Islam’s The Secret History Between Blacks and Jews, namely that Jewish financial interests dominated the African slave trade. Full disclosure, I haven’t read the NOI’s book, but I have read several books by the eminent historian of African slavery, David Brion Davis, and trust him when he says the accusation is greatly overplayed. Were there Jews involved? Of course. Everyone in Western Europe was getting in on the action, and the Jews are part of “everyone.” Another commenter (Pablo) may have given the best answer to the question of Jewish involvement in the slave trade: “More than mainstream history is comfortable with and less than (antisemites) think.” Did they “control the slave trade?” No, and I would encourage anyone with doubts to at least grapple with the points Davis makes in the article I linked above.

Karl asks, “If we’re recycling all the the dumb, rich-kid-radical ideas of the 60s now, but with millennials and zoomers, are we going to repeat the whole 60s-70s-80s cycle again, though faster and with fewer resources? In other words, if… now we’re into the urban decay/energy crisis/silent majority 70s, can we expect some sort of “the pride is back” 80s vibe to roll in around 2030?”

I’ve thought about this a lot, and if so it is a frightening prospect. By 1973, the country’s mood had shifted away from the excesses of the ‘60s, but it still took another twenty years of decline before people found the will to turn things around.

You know what, I’ll get into this more in the next post. Sorry guys, I’ve given myself a headache staring at that Pollock, so I’m gonna wrap it here for now. Thanks for reading, and please consider becoming a paid subscriber for just $5 p/month or $50 p/year.

*Sidenote* I’ve been working lately on two longer-term projects - the next Whose America history episode, and another long piece for Substack - as well as some new Unravelings that Jocko and I will record next week. These things have been taking most of my time, and that’s why my recent posts were less involved than usual. I do have a really good story to read to you guys, though, and I’ll release that this weekend sometime.

I just re-upped my subscription for a 2nd year, and articles like this are why (completely separate from the also-worth-it Jonestown & Whose America podcasts). Particularly struck by:

1. Roman parallels to modern America: onetime successful landowners displaced by mass immigration, which drives down wages and consolidates enterprise in a few powerful hands while relatively impoverishing others. I was once a loathsome radical libertarian who believed “complacent” Americans had no right to labor that could be done for half price by an immigrant. Now I understand that, “yeah, if I were supporting my family on $40/hr, and now a Guatemalan will do any of those jobs for $20/hr, I’m not taking a 50% pay cut, selling my house and never taking another vacation for the luxury of keeping my job.” The bipartisan free market view of the 80s, 90s and 00s is an economically correct one that has gutted the country and strip-mined its culture, because it is an incomplete/utopian vision of progress.

2. The geographically mobile economic nomad point. Our family has done well with this but you’re right: “local” culture and values are mostly extinct, replaced by hyper mobile paycheck-mercenaries. There was an old PBS special in which a northeastern linguist-academic lamented the disappearance of Philadelphia’s (and PA’s) *multiple* accents, which were different even between neighborhoods in Philly. If only she could have lived to see that most Texans you meet no longer even have an accent. And values, once local, and inculcated locally in schoolrooms and churches and civic clubs, are now national/international, and inculcated on screens and enforced by Western intelligence communities.

3. The idea that your gardening windfall (“it’s the same price for me to buy from WMT as it is to tend a garden”) is understandably shrug material for you, but panic material for any non-corporate farmer. As soon as that’s true, it’s lights out for millions

4. CIA involvement in culture. The more I read about the IC of the midcentury, the more I realize that the virtuous America I fought for as a Marine in the 00s probably hasn’t existed since WWII, and maybe not even then. To think that the Church Committee failed to address most of it, and what it did address largely just encouraged the IC to be more covert in its activities, and that they’re now gaining confidence that they can be bolder in their strong-armed tactics as it seems nobody can/will stop them...

“Someone who moves from Austin to Los Angeles for work, and may move again if the right opportunity arises, does not have a home in either place, even if he owns property in both cities.”

Very true. Have you heard any of VDH’s recent talks on his book “the dying citizen”? Really changed my perspective on citizenship, property, class, and politics.