The Peculiar Institution, pt. 13

A history of violence

Hey everyone. Here’s part 13 of our ongoing series on the history of slavery and the leadup to the US Civil War. I realized yesterday that I’ve written about 150 pages over the course of these 13 installments, with probably another 6 or 7 installments coming, so it amounts to doing an entire book, chapter by chapter. There are a lot of other things I have been wanting to cover, so next time I do a series like this I’ll put more work into planning it out before I start, so I don’t get quite so carried away. In any case, if you follow me, it’s because you like deep dives, not snorkeling on the surface, so I hope you’re getting something out of this series. Lots of big, big news coming up, but I’ll announce it as things solidify. I will record the audio version of this episode tomorrow.

To all my paid subscribers, I never know what to say except thank you, and thank you again, so, again, thank you. You are the reason I do this, and the reason I’m able to do it. I can pay my electric bill and buy my cat expensive food to accommodate his sensitive stomach so that he doesn’t fart while purring on my lap, and that is all thanks to you.

To our unpaid subscribers, I know it might seem weird to jump in when I’m on part 13 of a series, but check it out: paid subscribers have access to the audio versions of every installment, which post to private feed on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or whatever you use to listen to podcasts. So you don’t have to read 13 long essays to catch up, you can listen to the podcasts like 13 chapters of an audiobook. It’s just $5 a month, or $50 a year, and there’s a backlog of probably 50 or 60 podcasts you haven’t heard unless you’re a paid subscriber, so give it a shot and help keep Martyr Made going!

When England established the colony of Carolina in 1663, slavery was still something of rarity in British America. It was only around that time that life expectancy had increased to a point that purchasing a slave was becoming more economical than purchasing a servant, and most slaves marketed in the New World were snapped up by the more profitable sugar colonies in Brazil and the West Indies. Black slaves were around, people weren’t shocked to pass one on the road, but the vast majority of plantation labor was performed by white servants and tenants.

Prominent among the early colonists of Carolina were settlers from Barbados, many of them Dutch and converso slavers who’d come to Barbados from Brazil, and brought with them an intimate knowledge of not only the cultivation and marketing of sugar, but also of the African slave trade. Whereas no other American colony began with slavery in mind, Carolina was a slave society from the start, as planters brought their labor force with them from Barbados. Within a short time, Carolina was England’s most profitable mainland colony, by far. The other colonies looked on with envy, but there was little they could do since a series of conflicts between the English and Dutch hampered the transatlantic slave trade (which was controlled by the Dutch), and the Royal African Company set up by the English proved unable to fill the gap. In the 1670s, at the time of Bacon’s Rebellion, Carolina remained the only colony that used slaves to perform most of its labor.

The rest of the colonies came around to the idea of mass slavery toward the end of the century, but, once it began, the transition happened very quickly. The move from servants to slaves happened so fast that it gives the impression of a top-down program, but in fact there was no high-level coordination at all. No one called together elite planters and made the decision to become a slave society - and if such a vote had occurred, it very likely would have been rejected. The transformation into a slave society was accomplished bit by bit, by individual planters acting on their own initiative, for their own near-term benefit. A slave labor force cost more up front than a similar number of servants, but their upkeep cost less. Servants had to be replaced after 5-7 years, there was a long tradition of English common law protecting servants’ rights, and limiting the masters’ power over them. No such body of law existed regarding the treatment of slaves, because slavery was something to which the English had only recently been reintroduced. The upshot was simply that slave-worked plantations had a huge competitive advantage over ones worked by servants, especially over the long-term, which meant if one planter made the move, his neighbors had to follow him just to keep up. The demands of a competitive market turned out to be a much more powerful motivator than a top-down program imposed without the buy-in of the men on the ground, and by 1708 it was already being reported that virtually all of the bonded laborers imported into Virginia were enslaved Africans.

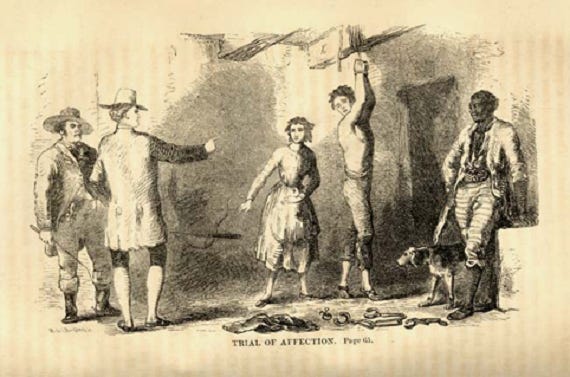

The transition from servants to slaves was smoother and easier than might be assumed, since few changes had to be made to the existing system of indentured servitude. Plantations already had separate barracks or quartering houses for their servants. Servants were already supervised by overseers in work gangs of eight to ten men. They were already subject to whipping and other forms of corporal punishment, they were already often underfed and poorly clothed, and their masters already lived in fear of sabotage and rebellion. The only change the planters had to make was to start purchasing slaves instead of servants, then plug the slaves directly into the existing system. In fact, until the number of servants dried up, black slaves and white servants usually worked together, lived together, ate together, got drunk and complained about their overseers together

Within a few decades, slaves went from being an oddity in English America to a common sight in almost all the colonies. Even the French governor of Canada had dreams of creating an agricultural slave empire in his territory (which failed spectacularly). Climate and geography limited the large-scale usefulness of slaves for agriculture in the north, but they were still put to work in a variety of other ways. By the 1750s, slaves would constitute 15-20% of the population of Newport (one of America’s two main slave trading ports) and New York City (partly as a legacy of the period of Dutch rule), and it was estimated that at least one in ten New York households owned slaves.

How, and to what degree, each region adopted slavery was a question of the supply and demand for labor. Massachusetts had a ready supply of Puritan refugees, whose theology elevated earthly work to a religious duty, paired with a climate that didn’t lend itself to plantation agriculture. Slaves could still be found in urban trades, basic labor, and household service, but they were never in great demand. When New York City was controlled by the Dutch and called New Amsterdam, slavery became an integral part of the colonial economy very early, since there wasn’t a large pool of religious refugees from which to draw, though the scale was still limited by climate and geography. Only the southern colonies were suitable for the large-scale plantations that made mass enslavement profitable.

From the beginning, American slavery was so diverse that it is difficult to compare it to the slave systems of Brazil or the Caribbean islands, where the practice was more uniform. When most people think of American slavery, they invariably imagine a cotton plantation in the Deep South, but cotton was adopted as a staple crop relatively late in the game. Before Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin in 1805, virtually all American slaves were still located on the Atlantic coast, especially in Maryland, Virginia, Carolina, and Georgia, where they grew tobacco and rice, cleared forests and dug irrigation, raised livestock and cut firewood, and engaged in skilled trades of all kinds. Slave life before and after the cotton revolution were very different, and it is a mistake to reduce the entire history of the practice to the factory-style cotton plantation. Even in the same era, slavery in Virginia was different from slavery in Carolina and Georgia, and all three were different from slavery in the West and further north.