The Peculiar Institution, pt. 16

People tend to resist historical narratives that downplay or evade the importance of human agency. Deterministic explanations make a mockery of our illusions of control, and leave little room for Good vs. Evil morality tales. On the other hand, intellectuals often love historiography that deletes unpredictable variables like will and courage, fear and cowardice, love and hate, and calls on their cleverness and ingenuity to design a unified theory of history. The most famous of these is, of course, the dialectical materialism of Karl Marx, but you can find attempts to make pretty much any variable into the hub around which the wheel of history turns.

The truth is that history is less like a wheel than a web. Touching any point on a web causes every other point to shift. With enough information, the shifts are predictable, but when the web is vast and being touched in many places (some of them hidden) at once, our interpretive systems are quickly overwhelmed. Without a reliable framework for predicting the future and explaining the past, human choice, which is it at least visible and familiar, looms larger in the foreground.

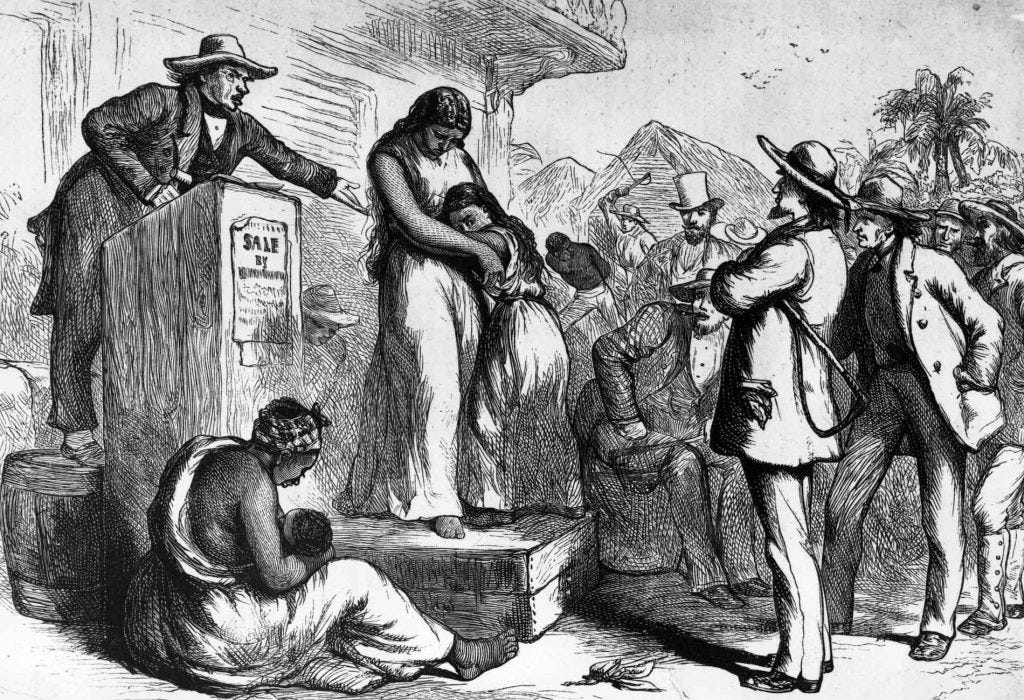

I have made the case throughout this series that slavery in the New World was inevitable from the moment Columbus returned with news from his first transatlantic voyage. Countries that took advantage of New World colonization would overwhelm countries that didn’t, therefore the New World would be colonized. All it took was one country to do it, and the rest were faced with the choice of joining the game or leaving the field. Since no country in Europe had a sufficient population to colonize the New World with just its own people, colonizers had no choice but to avail themselves of alternative sources of labor. Spain and Portugal found the New World first, and happened to be from a region that, unlike northwestern Europe, had had unbroken experience with slavery for all of its recorded history, and most recently with the West African slave trade. Finally, the Iberians inherited a thoroughgoing ideological defense of racial slavery from their Muslim neighbors, and no opposing framework existed anywhere in the world. There were no international institutions to mediate an agreement to eschew slavery, and no ruler powerful enough to compel others to abide by it. In the absence of certainty, each power had no choice but prepare for the worst by snatching the advantage before it was used against them. All this is to say that, while the details of New World settlement were shaped by chance and human choices, the limits of their influence were set by larger forces.

Americans of the revolutionary generation were born into a world slavery had created. By 1776, transatlantic slavery had matured into a complex, interconnected system with a decisive role shaping events on four continents. It’s been said that people today find it easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism or liberal democracy. The same could be said of how people viewed slavery for most of human history, but that was changing as the 18th century rolled over into the 19th. The British Empire remained the world’s dominant power, and, although the British controlled the slave trade, losing the American South to the revolution altered the balance of costs and benefits of the trade. While the British derived healthy profits from the trade, they were less dependent on it than their chief rivals. The French colony of Saint-Domingue (Haiti) produced more sugar than the combined output of Brazil, Cuba, and Jamaica - the most important sugar colonies of Portugal, Spain, and Britain, respectively - and was the one reliable cornerstone of an economy wobbling on the edge of disaster. Spain and Portugal were similarly dependent on their New World slave industries. So, an end to the slave trade would mean a small hit for Britain, but, at least in theory, a much larger one to its rivals and enemies. Finally, the general massacre of whites and destruction of property during the Haitian Revolution put everyone on notice that slavery’s hidden costs might come due unexpectedly, and all at once. As the balance of slavery’s costs and benefits became an open question for Britain, voices calling for the end of the institution grew louder, more numerous, and more assertive.

When the Founding Fathers came together in Philadelphia to hammer out the US Constitution, there were good reasons to believe that slavery was decreasing in importance, and would continue to decline until its end became a mere technical question. This belief was so widespread that even the strongest opponents of slavery among them felt comfortable putting the question aside, and its most ardent defenders withdrew their opposition to ending the importation of new slaves after 1808. Before the ink of their signatures was even dry, though, everything changed.