The Peculiar Institution, pt. 3

Hi everyone. Much of this installment was meant to be part of the previous one, but I broke it up in the interest of time. So this one will complete the discussion started in the last essay, and I’ll try not to rehash anything unless it’s necessary for clarity.

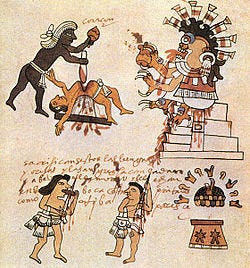

When Christians began to penetrate into Africa and the New World, they discovered societies unlike anything they’d ever seen, or even imagined. From Africa to Melanesia, across the Pacific to Old Mexico, European explorers were discovering tribes of naked savages, and civilizations engaged in human sacrifice and cannibalism, practices their religious books said had been stamped in prehistory by the armies of God. These encounters imbued the European Christians with a sense of confidence in their global civilizing mission. Not since the Crusades - and perhaps not even then - had conquest ever felt so righteous. Let’s look at a few examples, and try to put ourselves in the shoes of the European discoverers.

J.G. Frazer, in his book The Golden Bough, summarized an account of the September maize festival practiced by the Aztecs:

(The) great festival… was preceded by a strict fast of seven days, (after which) they sanctified a young slave girl of twelve or thirteen years, the prettiest they could find, to represent the Maize Goddess Chicomecohuatl. They invested her with the ornaments of the goddess, putting a mitre on her head and maize-cobs round her neck and in her hands, and fastening a green feather upright on the crown of her head to imitate and ear of maize. This they did, we are told, in order to signify that the maize was almost ripe at the time of the festival, but because it was still tender they chose a girl of tender years to play the part of the Maize Goddess. The whole long day they led the poor child in all her finery, with the green plume nodding on her head, from house to house dancing merrily to cheer people after the dullness and privations of the fast.

In the evening all the people assembled at the temple, the courts of which they lit up by a multitude of lanterns and candles. There they passed the night without sleeping, and at midnight, while the trumpets, flutes, and horns discoursed solemn music, a portable framework or palanquin was brought forth, bedecked with festoons of maize-cobs and peppers and filled with seeds of all sorts. This the bearers set down at the door of the chamber in which the wooden image of the goddess stood. Now the chamber was adorned and wreathed, both outside and inside, with wreaths of maize-cobs, peppers, pumpkins, roses, and seeds of every kind, a wonder to behold; the whole floor was covered deep with these verdant offerings of the pious.

After rituals of cleansing and thanks, the girl was taken down from the scaffolding and led to the place where she was to spend the night. The people remained in the court keeping watch by torchlight until dawn, which brought new rounds of ritual and worship, until finally:

The multitude being assembled, the priests solemnly incensed the girl who personated the goddess; then they threw her on her back on the heap of corn and seeds, cut off her head, caught the gushing blood in a tub, and sprinkled the blood on the wooden image of the goddess, the walls of the chambers, and the offerings of corn, peppers, pumpkins, seeds, and vegetables which cumbered the floor. After that they flayed the headless trunk, and one of the priests made shift to squeeze himself into the bloody skin. Having done so they clad him in all the robes which the girl had worn; they put the mitre on his head, the necklace of golden maize-cobs about his neck, the maize-cobs of feathers and gold in his hands; and thus arrayed they led him forth in public, all of them dancing to the tuck of drum, while he acted as fugleman, skipping and posturing at the head of the procession as briskly as he could be expected to do, incommoded as he was by the tight and clammy skin of the girl…

Now, the conquistadores were hard men, soldiers who did not shrink from blood or violence, and yet we know from their accounts that what they found in Mexico shook them to their core. Bernal Diaz, who was there for Cortes’ expedition and documented it in his book The Conquest of New Spain, writes of the Spaniards’ experience after a battle went against them. The survivors had barely escaped, and several of their comrades had been captured. Day after day, as the Spanish laid siege from a reasonable distance, they watched their friends meet their fate:

The dismal drum of Huichilobos sounded again, accompanied by conches, horns and trumpet-like instruments. It was a terrifying sound, and when we looked at the tall cue from which it came we saw our comrades who had been captured in Cortes’ defeat being dragged up the steps to be sacrificed. When they had hauled them up to a small platform in front of the shrine where they kept their accursed idols, we saw them put plumes on the heads of many of them; and they made them dance with a sort of fan in front of Huichilobos. Then after they had danced, the papas laid them down on their backs on some narrow stones of sacrifice and, cutting open their chests, drew out their palpitating hearts, which they offered to the idols before them… (The Conquest of New Spain, volume II, chapter 152).

I must say that when I saw my comrades dragged up each day to the altar, and their chests struck open and their palpitating hearts drawn out, and when I saw the arms and legs of these sixty-two men cut off and eaten, I feared that one day or another they would do the same to me. Twice already they had laid hands on me to drag me off, but it pleased God that I should escape from their clutches. When I remembered their hideous deaths, and the proverb that the little pitcher goes many times to the fountain, and so on, I came to fear death more than ever in the past. (The Conquest of New Spain, volume II, chapter 156).

Hugh Thomas, in his excellent book Conquest: Montezuma, Cortes, and the Fall of Old Mexico, writes:

This repeated discovery of… human sacrifice concentrated the minds of the conquistadors… The Castilians in Mexico now realised the danger in which they would be if they were so unfortunate as to fall into the hands of the Mexica. This appreciation had a profoundly shocking effect, permanently souring relations with the Indians and causing the Castilians to adopt an unbending attitude in negotiations. Sacrifice was far from being merely a pretext for intervention. Aguilar (not the interpreter Aguilar), a member of the expedition, made this evident: “To my manner of thinking, there is no other kingdom on earth where such an offence and disservice has been rendered to Our Lord, nor where the devil has been so honoured.”

If Aguilar had been more well-traveled, he would have seen that the devil was similarly honored on every continent, by people who matched the Aztecs’ brutality, if not their creative elaboration and refinement.

Further north, among the Huron of the Great Lakes region, we find this: