The Rise and Fall of the Partnership for Peace, pt. 3

Third part of a series about post-Cold War US-EU-Russia diplomacy

This is the third part of a series on post-Cold War US-EU-Russia diplomacy. The previous installments are available here (part 1), and here (part 2).

When the Partnership for Peace first began to take shape, enthusiasm from Bill Clinton and Boris Yeltsin initially muted the naysayers. The Department of Defense and PfP’s other supporters hailed it as a moderate move toward European integration that would provide most of the benefits of NATO membership, without creating unnecessary tension with Russia. The Clinton administration was all-in on Boris Yeltsin, but he was not without rivals in Russia, and breaking our promise not to expand NATO so soon would make Yeltsin look weak and empower his hardline opponents. Russia was among the first of fourteen (of an eventual twenty) states to join the PfP in 1994, and for a moment it looked like brighter days lay ahead. But only for a moment.

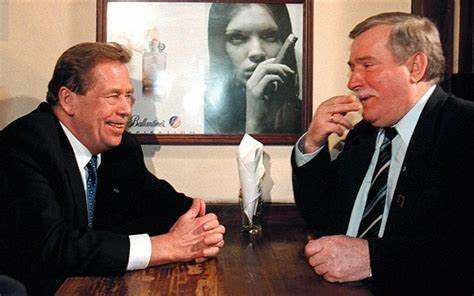

From the beginning, the enemies of PfP were many, and they were motivated. First among them were the Central and Eastern European states themselves. They wanted into NATO, not some junior partner NATO-lite like the PfP. Getting into NATO would not only provide economic and security guarantees, it would ensure their equal status as members of the European community. Central and Eastern European countries were not interested in an arrangement that placed them on equal footing with Ukraine, Belarus, and the rest of “what they perceive to be the less advanced states to the east,” as a US diplomatic cable reported. Cold War propaganda had turned leaders like Vaclav Havel of the Czech Republic and Lech Walesa of Poland into sainted celebrities, and their words could be put to damaging use against any Western leader who was hesitant about a headlong rush toward NATO expansion. Among PfP’s domestic opponents was Henry Kissinger, and his criticism was the shared basis for most of the PfP’s opponents. While PfP’s backers saw its inclusivity as its biggest advantage (since it could bring together states that were not prepared, or ineligible altogether, for NATO membership), Kissinger and other opponents were against any arrangement that didn’t treat Russia - not the Soviet Union, which didn’t exist anymore, but Russia - as a defeated enemy. In Kissinger’s words, Russians had been the “perpetrators” of Soviet crimes, while all other countries in the Eastern Bloc had been its “victims,” and it would be unacceptable to ask the victims to sit side-by-side as equals with their former oppressor.