Confrontation, pt. 2 - The Book of Job

“As flies to wanton boys, are we to the gods. They kill us for their sport.”

Shakespeare | King Lear

This is part 2. Part 1 can be found here.

This series was prompted by a mini-uproad I recently caused among some of my followers on Twitter. Someone asked, “What is something you think that almost no one agrees with you about?” I replied: “God is the villain in the Book of Job.” I invited the backlash by putting it so provocatively, but hey, backlash counts as engagement too. Do I really mean it, though? Hmm… maybe. I’ll try to explain.

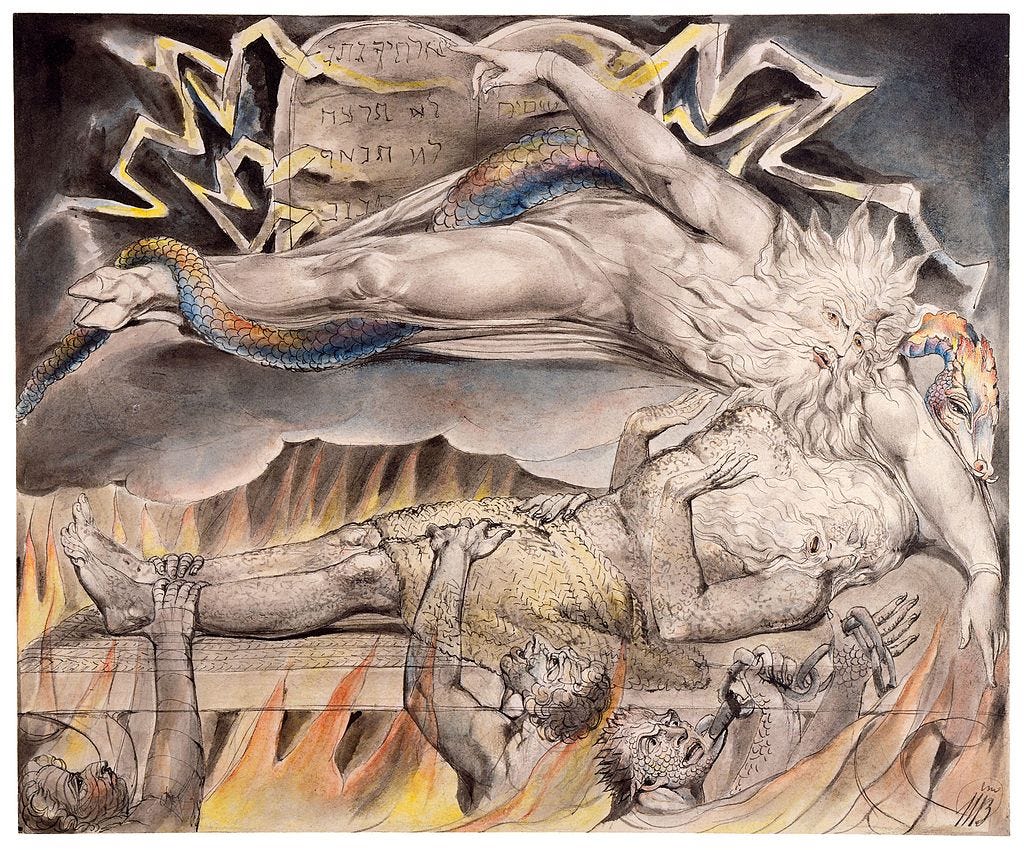

If God were anyone other than God, there would be no question of how to judge His behavior toward Job. Imagine a husband who tortures his loving wife to satisfy his paranoia regarding the unconditionality of her loyalty. Imagine that she does not retaliate, does not even curse her husband, but only weeps and asks for an explanation, but, rather than explain himself, he only shouts, “I am twice your size! I could snap your neck with my bare hands! Who do you think you are to question me?” Would there be anyone who cared to raise their voice in defense of the husband? Of course not. Or, imagine a king gratuitously harms his loyal subjects - in fact, his most loyal subject - for the same reason. The gulf separating a king from his subjects is much wider than the gulf between husband and wife. Does the king’s greater power and position mitigate his moral guilt relative to the husband? The husband’s justification was that his greater power relative to his wife meant that she could have no valid claim against his conduct, and no right to expect his behavior to conform to any standard. If we accept this defense from the husband even a little bit, then the same argument ought to mitigate the guilt of a king even more. Most of us would say no, both the husband and the king are equally, totally, indefensibly guilty. But this is, in so many words, the answer God gives to Job, and orthodox readings of the Bible do accept this non-explanation as right and reasonable.

During his discussions with his friends, Job had, on more than one occasion, evoked a courtroom scene and demanded to face his accuser:

If only I knew where I might find him,

that I might stand in His place of dwelling!

I would present my case before Him,

and fill my mouth with arguments.

I would find out what answer He might give,

and consider what He would say to me.

Would He contend with me by the greatness of His power?

No! He would hear me out, and drop all charges against me.

For there the upright can get a fair hearing,

and I would forever be delivered from my Judge.1

Essentially, what Job is saying is that there must be some mistake, because he’s innocent of whatever it is that’s brought this punishment upon him. Job’s uprightness was established at the beginning of the story, and is not in question. What is in question is whether his uprightness has anything to do with how God chooses to behave toward him. Job thinks it should, and he didn’t pull that notion out of a hat. Half of the Old Testament consists of God assuring His people that if they do right by Him, then He’ll do right by them. The other half consists of God warning them of the consequences of failing to meet His expectations, and He certainly makes good on this end of the bargain when they slip up. But Job has not slipped up. He is not only a good man, but the best man, “upright and blameless and there is no one like him in the world,” says God. If anyone is within his rights to expect God to keep his promises and deal fairly with him, it’s Job.

God Himself boasts to Satan of Job’s steadfastness after the first round of torture: “See, he has held fast to his innocence, even after you incited me to ruin him without cause.” Job had taken the massacre of his family and the destruction of his property with stoic humility, saying that he had only had those things because the Lord had provided them, so it was the Lord’s prerogative if He decided to take them back. It is only when Job has been reduced to a despised, penniless beggar, sitting in ashes, mourning his murdered family and scratching with a potsherd the sores that cover his body, that Job mounts his challenge.

Job had faith that he would be vindicated if only he could stand before God and prove his innocence, but his insistence cannot help but be an accusation. If Job is innocent, then God is guilty of unjustly giving him over to torture. This is the blasphemy that outrages and alarms Job’s three companions, but Job refuses to back down, and eventually reduces them to silence, prompting God to make an appearance to speak on His own behalf. Someone unfamiliar with the Book of Job, but familiar with the rest of the Bible, might expect God to offer Job something by way of explanation. But what explanation could he possibly give? Admitting that He’d been duped by Satan would make Him no better than Adam and Eve, whom He cursed and barred from His presence after they fell for the devil’s tricks. He could even claim to have had reasons beyond Job’s comprehension for what He had put him through - which would be less satisfying to Job, no doubt, but at least has the benefit of being believable. God gives Job nothing of the kind, but simply refuses to answer his questions at all.

The Psalmist poses a good question:

When I consider your heavens, the work of your hands,

The moon and the stars, which you have set in place;

what is man that you take thought of him,

or human beings that you show them concern?2

Another way to phrase the question might be, “What are you getting out of this relationship?” It’s pretty clear what man gets out of it - first and foremost, we get to exist. But what about God? A plain reading of the Old Testament makes it seem as though we’ve been a profound disappointment and a thorn in God’s side ever since He shaped us from the dust of the ground. For the first five days of creation, everything went according to plan as God effortlessly spoke the universe into existence. On the sixth day, God created man, and right away we’re told that there was something wrong with him - namely, that “it is not good for him to be alone.”3 A minor flaw, perhaps, but the first one in all creation recorded thus far into the story. God parades all the animals of the world before Adam so he can name them, and to evaluate whether any of them would serve as a suitable companion for him. None of the animals meet the requirements, though, so God realizes that Adam needs someone a little more like himself. So he puts Adam to sleep and creates Eve from one of his ribs. On the seventh day, God rested - did the act of creation take more out of Him than Chapter One seemed to admit? - and it didn’t take long for the humans to find trouble.

We all know the story, right? When God planted the Garden of Eden, He told Adam and Eve that they could eat any fruit or seed from any plant in the place - except for one. Why would He do that? That is, why put the tree there at all? Adam and Eve are only about a day old, so it seems a bit like leaving a poisoned candy bar with a child. Actually, it’s like leaving a poisoned candy bar with a child and then sending an older sibling already notorious for causing trouble to convince the child to eat it. Who, in this case, would be responsible if the child did eat it? Of the three - the parents, the older sibling, and the child - I think most people would say that the child bears the least responsibility, followed by the older sibling (the serpent), and that final responsibility would fall on the parents for engineering the whole scenario in the first place.

Why did God let the devil into His brand new Garden to harass His newest creations? The most obvious answer is that the serpent and the tree were put there to test us, and it’s an explanation that fits well with the rest of the Old Testament story. But why? Well, try to see things from God’s perspective. Up until the creation of man, every single phenomenon in the whole history of the universe had bent instantly to God’s will, operating according to the ordering principles he’d worked out from the first cosmic moment. Then, one day, these little human creatures decided to go off script and start doing their own thing. So God watches with interest as the little troublemakers spread out on the earth (indeed, what could be more interesting to a being for whom every other thing in the universe had always been perfectly predictable?). The humans build a great big tower, and God decides they’re getting a little big for their britches and knocks it over. Before long, the fascination fades and God begins to tire of their rebelliousness, and kills all but a handful of them with a great flood.

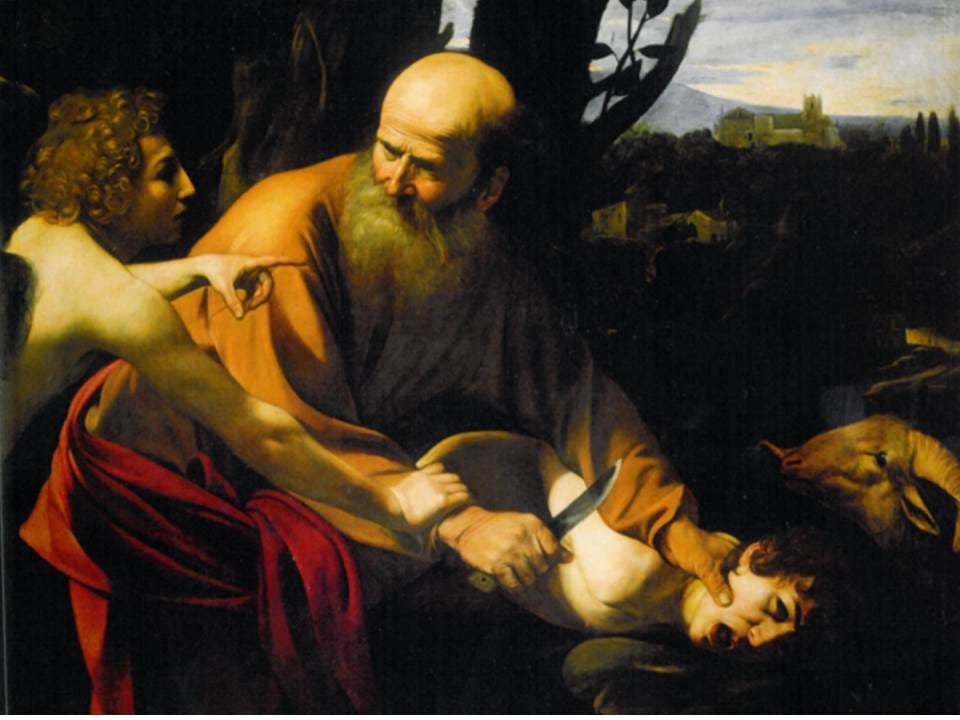

A little later, God finds a man named Abraham and orders him to kill his son Isaac. Why? Well, to see if he would do it, I guess. God’s doubt regarding Abraham’s loyalty is only allayed when Abraham has the knife raised for the killing strike, and at the last moment He calls it off. In a world of rebellious men, Abraham has proven his obedience. God makes a covenant with Abraham, promising to look after his line and ensure its prosperity just so long as his descendants continue to replicate Abraham’s mechanical obedience. But is that what He really wants? He can get blind obedience from his angels or any of his creatures. The whole reason God takes such an interest in us is that we’re the only beings in all creation capable of surprising Him. This is made clear in the story of Abraham’s grandson Jacob.

One night, God comes to Jacob, and they wrestle or fight with one another in the darkness. The match continues all night, and neither can decisively overcome the other. Seeing that Jacob would not go down to defeat so easily, God eventually puts his hip out of socket (an injury that would cause Jacob to limp for the rest of his life). Still Jacob would not tap out, and so God finally resorts to pleading with Jacob to release Him (“Release me, for dawn approaches!”). Jacob refuses, saying he will not let Him go unless God blesses him, and the Lord apparently has no choice but to concede and give Jacob what he wants. As part of His blessing, God changes Jacob’s name to Israel, “for you have contended against God and man, and have prevailed.”4 The name Israel means “one who struggles against God.” Think of it, the chosen people of God, their very name refers to the fact that they are capable of resisting him. This is a remarkable aspect of the Bible story. For all eternity up until the creation of Adam, God had been alone in the universe, nothing in existence except Him and His toys, every molecule racing to fulfill His whims as soon as He conceived them. Then one day emerged this little creature that looked Him in the eye and caused God to realize that He was no longer alone. What, if not man, could hold His interest? Perhaps this is the answer to the Psalmist’s question.