The God of Myth - A Meandering Detour from the Book of Job

I don't know exactly where I'm going with this, but I wrote it, so here you go

In the first part in this series, I mentioned that there was one thing about which most believers disagree with me, namely, that God changes over the course of the Old Testament. Even many people who might agree that God appears to change often fall back on the argument that it is not God who changes, but only man’s perception of Him. They may be right, but let’s continue a little further down the path of reading the Bible as a work of literature in which the character God is the protagonist.

The earliest apparent change in the divine nature happens during the Creation story itself. The first few chapters of Genesis, if taken at face value, seem to give an account that differs somewhat from the popular version of the universe’s first few days. Genesis 1 describes the creation of the universe from the void. Since God didn’t yet have anyone to hold the flashlight while He worked, His first act as Creator was to cause light to appear. The biblical phrase, “Let there be light!” is more imperious-sounding than the original Hebrew, for which a justifiable translation would simply be, “Light!” Interestingly, He doesn’t create the sun, moon, or stars “to give light on the earth” until Day 4, so I wonder if we’re supposed to read something else into “Let there be light!”

Consider the creation story in the Indian Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (composed 6-7th century BC). “In the beginning there was nothing whatsoever.” Then, just as in Genesis, came the first act, and the process of Creation got underway. The first act in the history of the universe could only have been one thing, and the Upanishad records it as, “Let me have a mind,” or, “let me awaken.” All of these make the same point, that Creation commenced with the emergence of consciousness, and light is probably the most common metaphor referring to consciousness (e.g., “the lights are on but nobody’s home). Are we meant to read the biblical First Act (“Let there be light!” or “Light!”) not as the emergence of light per se (which the Hebrews knew perfectly well came from the sun, moon, and stars), but as the emergence of consciousness?

The Upanishad continues, “In the beginning there was nothing whatsoever, but only Death, and hunger covering the whole world, for hunger means death.” Hunger causes death coming and going, and puts every creature on the horns of an eternal dilemma: to kill or be killed, to eat or be eaten? But how could the world be covered by death and hunger if there was nothing yet existing to die or be hungry? For endless ages before the first mind awoke, there was nothing at all happening except sex and death, every creature devouring every other that fell within its grasp, and the “visceral psychology of hunger” (Neumann) ruled we might call “consciousness” in the pre-human age. Perhaps the “beginning” in this story does not refer to the eternity before the world was formed, but of the time before the first consciousness emerged to contemplate it. The world we see around us only appears as it does because our nervous system has evolved to perceive it this way. With no one around to behold it, the universe is just energy, infinitesimal particles that don’t “look like” anything until they’re processed and rendered by consciousness. There are no objects, there is neither time nor space in the sense most people mean by those terms, there is no cause and effect; these phenomena are qualities of consciousness, a particular way of perceiving reality that allows an organism to get what it needs to survive and grow.

Wittgenstein once wrote, “The limits of my language are the limits of my world… Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” Homo sapiens didn’t come with complex, elaborate language right out of the box. There was a time, presumably, way back when our ancestors were emerging from ape-hood, when humans only possessed a single word, or maybe a few words. For most of human history, language developed to help us communicate and cooperate within and among groups to secure territory, to avoid and fend off danger, and to find and defend food and other resources. An enormous amount of cognitive and linguistic development had to take place before humans could begin to ask even a simple abstract question like, “How would you feel if you didn’t have breakfast this morning?”

Ancient languages often resort to metaphor because they lack the vocabulary to discuss abstract ideas directly. Even we moderns often use a term like “consciousness” without knowing exactly what we mean by it - or, rather, we know what we mean, but would have trouble defining it without resorting to synonyms like “mind”. The tabletop game Taboo is built around the difficulty we have describing even everyday words without falling back on synonyms, analogies, and metaphors. Imagine trying to describe the process of evolution, or the physics of the early universe, or ideas like “good” and “bad,” without recourse to abstract language or mathematics. Most of us would do what the ancients did, namely, try to explain it by means of metaphor and narrative. This is the reason myth preceded philosophy, and it’s the reason we teach children abstract concepts first by telling them stories, and only later by explaining the principles.

Chimpanzees have been observed engaging in rudimentary tool use, such as sticking a piece of straw down an anthill and drawing it back once it’s covered with yummy ants. This is not an instinctive behavior, and not all chimps do it; it’s a “cultural” trait taught to young chimps by their elders. Chimps, of course, have no verbal language1, so their only means of transmitting knowledge is by imitation. The same is true of very young children. The easiest way to teach a kid to tie his shoelaces is show him, to tell him to watch and do what you do. When a child develops a sufficient vocabulary, language can be used to supplement imitative learning. For example, some kids are taught a simple story (“Bunny ears, bunny ears, playing by a tree. Criss-crossed the tree, trying to catch me…”) as a mnemonic crutch for shoelace-tying if they can’t remember what they saw their parents do.

Moreover, narrative enables children to learn by imitating figures that exist only in their minds. They learn how to handle fear and develop courage and determination by hearing stories about courageous, determined people who overcame fear. Research has shown that children before the age of about seven lack the cognitive capacity - not merely the skill or ability, but the neurological hardware - to work fluently with abstract concepts. Trying to teach them to be good by way of Kant’s categorical imperative would be a wasted effort, and if you tried to do it you would almost involuntarily start telling them a very short story, like, “Being good is when you see someone who needs help, and you stop to help them.” Some lessons cannot be taught by imitation and require more precision than a metaphor can provide, but these are rarely relevant to a child. In fact, most adults can go through their entire lives and get along just fine without ever having much use for abstract theoretical concepts. Great civilizations were built by men who believed the sun was the wheel of a god’s chariot being driven across the firmament. The genius of the Greeks was that they took the giant step from understanding the world through narrative and metaphor (myth) to trying to understand it by means of abstract concepts (philosophy). In that sense, the Greeks may have been the first “adults” in history (at least in the world west of Persia).

The biblical Creation story was written down thousands of years ago, and was based on an oral tradition that may have gone back tens or even hundreds of millennia, when the human vocabulary consisted solely of terms related to practical experience. Those of us in the West whose concept of religious “belief” is based on Jewish and Christian traditions often struggle with the question of whether ancient pagans really “believed” their myths. After all, the Greeks could climb Mount Olympus and see for themselves whether Zeus and his court were anywhere to be found. They certainly believed their myths if belief means that their behavior was shaped by the stories. If belief is taken to mean that they took the stories literally, then it’s doubtful that they believed them in that sense.

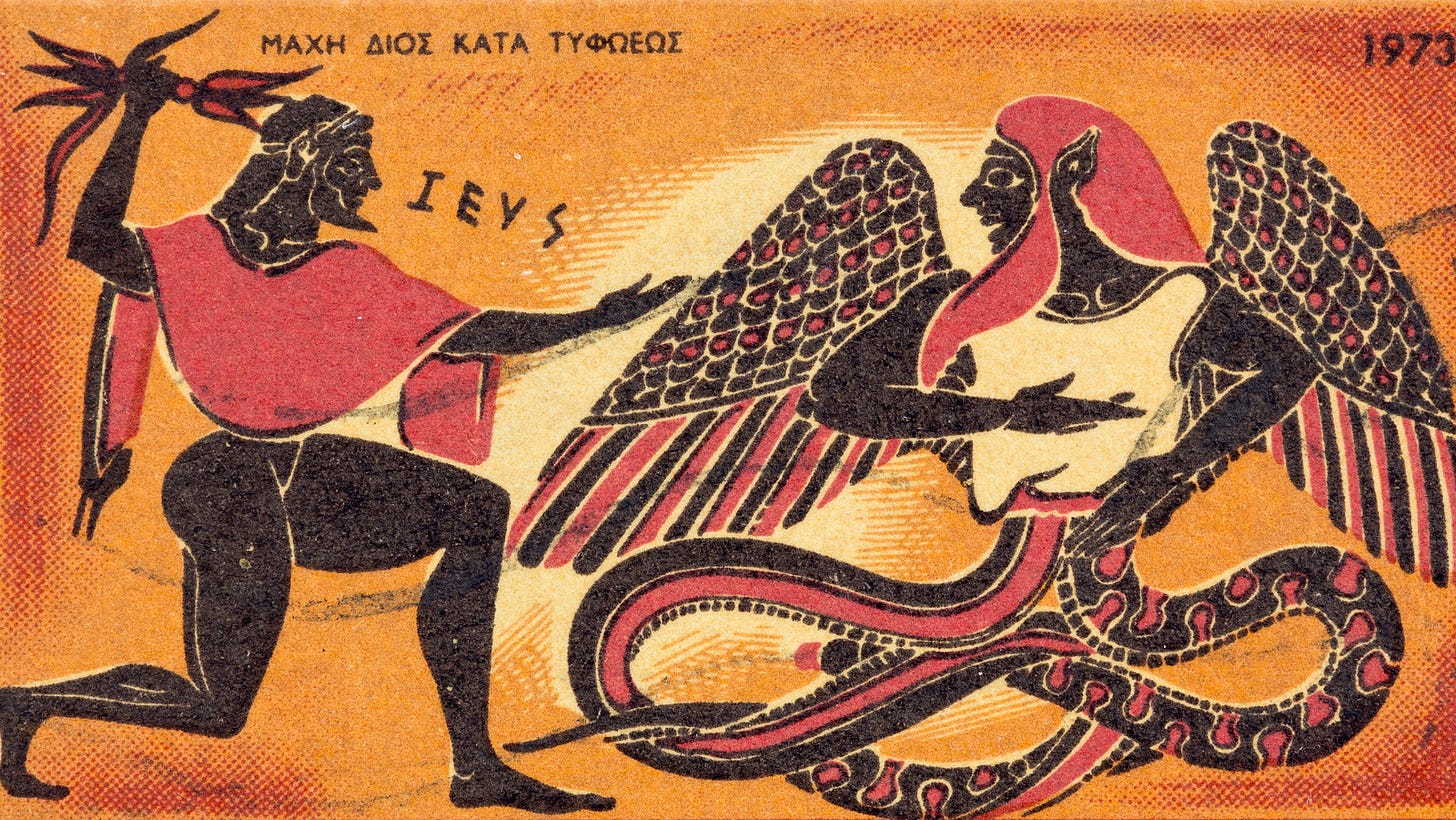

The core elements of most mythologies are almost unimaginably ancient. Greek myths were not original to Greece, but had their template among Aryan warrior-herdsmen of the south Russian steppe, the “womb of nations” whose conquests spawned civilizations from India to Greece, from Persia to Britain. We know the myths of these ancient civilizations had a common source because they share similarities which are otherwise inexplicable. For example, myths recounting an ancient battle between the thunderbolt-wielding king of the gods and an older, feminine water dragon/serpent are found throughout the Northern Hemisphere, anywhere reached by the proto-Indo-European migrations. For example, India has the story of Indra using his lightning bolt to strike down the water monster Vritra, who was preventing all the rivers and rains from nourishing the earth. Greece had the same story of lightning-wielding Zeus destroying the water monster Typhon. Norse mythology has the thunder god Thor in combat against the world-serpent Jörmungandr. The motif is found in Siberia, and even across the Bering Strait among some northern Native American tribes (most notably the Iroquois). This last diffusion suggests a truly ancient origin for the myth, since the last meaningful contact between the peoples of Eurasia and North America predates the last Ice Age. A similar motif is also found in Semitic myths in the Levant and Mesopotamia, suggesting cultural cross-pollination in the ancient Middle East. This is interesting, but not surprising, since Indo-European cultures - Scythians and other steppe peoples, Persians, Hittites, Cretans, ancient Armenians, and others - interacted through trade and conquest with the region’s Semitic peoples long before anyone began to make records of it. Indeed, the ancient Armenian homeland was the site of two prehistoric tales from the early chapters of the Book of Genesis.2 We find the Babylonian god Marduk casting his lightning bolt at the sea dragon Tiamat, and the Canaanite thunder god Ba’al doing the same against the serpentine sea-god Yam. Even in the Bible there are hints of Yahweh’s victory over the primordial sea beast (called Rahab in Job chapter 26, Isaiah chapter 51, and Psalm 89).

Well, you know what, we’re so far off track on this sidebar that I’m just going to keep going and we’ll get back to Job later. I only went off in this direction to suggest that the anthropomorphized, omnipresent, and all powerful God of the Bible could be an ancient storyteller’s way of expressing that fundamental reality operated more like a mind than a machine, but we’ll get back to that in the next installment. I’m on a mythological kick now, so I’m just gonna follow this stream of consciousness and see where it goes. I’ll try to keep it within boundaries that make it relevant to what’s coming next on the Job story.

While the mythological motif I described above is almost certainly an example of cultural diffusion, there are examples that, pending the discovery of yet-unknown cultural exchanges, can only be explained by independent, parallel development. In linguistics this phenomenon is called a false cognate - that is, similar words that indicate the same thing in languages that have no known historical connection to each other. The most famous cognate is perhaps the most well-known word on earth, and, for many of you, it might have been the first word you ever spoke: “ma.” You know, mother, mama, mum. Ma (or some close variation, such as mama or nana) refers to Mother in languages as diverse as English and Swahili, crossing boundaries not only of language, but of language groups. There are a few theories why this is so, but the simplest and most convincing is that ma is one of the first “words” a human infant begins to consistently generate. Ma is just the word that results when you make a sound with your lips closed, and then continue making the sound with your lips apart - mmmm-a… mmmm-amamama. This became associated with the mother because in every ancient culture Mother was the infant’s constant companion and its primary reference point throughout its early development. This might be counterintuitive. Today, we already have the word “ma,” so mothers try to teach their babies to call them “mama,” but originally it was probably the other way around. Before humans had a word for “mother,” the baby’s most common babble sound probably provided it.

The number of languages in which this phenomenon is present, and the rich linguistic, religious, and philosophical traditions that have grown out of it, indicate that ma is one of the most ancient words in the history of human language.3 In any case, there is a very high likelihood that not only English and Swahili-speaking kids, but also children of Paleolithic cave dwellers, called their female parent “mama” (or “nana”).

An infant is not born with a self-concept, nor any sense of subject-object differentiation, or even a sense of the world being made up of discrete objects. It has no identity, and no sense that the world outside is separate from its own being. It sees and hears, but, at first, does not know what it’s seeing or hearing. The experience of one moment has little connection to the next. It also has no sense of what is worth paying attention to, and what should be ignored. The world of the infant begins as a buzzing, flashing chaos with only one anchoring presence to hold onto. The first separate object of which the infant becomes aware is invariably its Mother, and, with that first recognition of an Other, the world, which had been an undifferentiated whole, is split into two. The Infant-Mother dyad is the basis of every human’s first cosmology. Eventually, the baby learns that the universe is neither its own undifferentiated self, nor the self-Mother dyad, but a more complex arrangement in which Mother is only one of countless objects and forces that populate its world.

The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, mentioned earlier in this essay, seems to recount this process in mythological terms. Immediately after the awakening of the divine mind, nothing else had yet been created. There was only the mind, and the mind was all there was, and since nothing else yet existed, the mind had nothing to contemplate but itself. But then, one day, the mind had a thought - the first thought in the history of the universe. The thought was “I,” or “I am he.”4 Indeed, what else could it be? There was nothing else but himself to think about, and, like the baby in the womb, the divine mind had presumably floated in unconscious bliss for uncountable eons (for time had not yet begun) before it became aware of itself as a locus of experience and will. This is the moment early in an infant’s life when, in its extremely rudimentary way, the child realizes that it is an individual. Everyone’s first thought (although they haven’t yet learned the word for it) is “I.”

As soon as that first thought happened, it immediately gave rise to another thought. The mind thought, “Well, now that I know that I exist, what if something should happen to me?” The automatic and inevitable consequence of having a self is fear. On the heels of this second thought followed a third, equally inevitable and automatic, which was, “Wait, I don’t have anything to be afraid of since I am here all alone.” That caused the fear to subside, but it was immediately replaced by a new feeling: “He was not at all happy. Therefore, people to this day are not happy when alone. He desired a companion.” Thus the two immediate results, inevitable and automatic, of having a self were Fear and Desire, and it was these impulses which caused the divine mind (God, in our Western way of thinking) to create the world. This is a central point in later Indian, especially Buddhist, mythology. According to the Upanishad, the desire for a companion was satisfied when he split himself in two and produced a woman, who was simultaneously daughter, wife, and mother. It is the story of Genesis, only told as if Adam was not merely an image of the Creator, but the Creator himself.

In old Sanskrit, the Indo-European language of ancient India, the root word ma means “to measure,” as in the important Indian cosmological term “ma-ya,” which means “to measure forth,” or, to measure and mark off the part from the whole. The Sanskrit root ma also means “to make”, “to create”, or “to bring forth.”5 Mother becomes more interesting as she continues to develop. From the root ma we also get matrix, which is defined as “a situation or surrounding substance within which something else originates, develops, or is contained.” In the typical Bronze Age cosmology, the central religious cult revolved around the goddess-as-matrix: that is, the goddess was herself the universe, time and space, the ma-trix within which we all live, breathe, and have our being. The gods were secondary, existing within the same structural matrix as mankind (though in a more exalted place in the hierarchy). In ancient Egypt, for example, the great sun god Ra, the solar disc, passed through the body of the goddess each night to be reborn again each morning. Heinrich Zimmer, a scholar who specialized in Indian mythology, commented on her manifestation here:

If one inquires to know her ultimate origin, the oldest textual remains and images can carry us back only so far, and permit us to say: ‘Thus she appeared in those early times; so-and-so she may have been named; and in such-and-such a manner she seems to have been revered.’ But with that we have come to the end of what can be said; with that we have come to the primitive problem of her comprehension and being. She is the primum mobile, the first beginning, the material matrix out of which all comes forth.

Also from ma we get mater (Latin for “mother”), matter, and material. The generative act of the human mother was perceived as a mere shade of the generative act of the earth goddess, and the association of the feminine principle with the realm of matter - that is, of life in the world, in time and space, in the cycle of birth, maturity, death, and regeneration - is ancient and widespread.

Should we be surprised? Woman is herself the embodiment of the deep, unfathomable mystery of life. She is the beating core, the actual main event, of everything going on around us. The cities men build, the art we create, the stories we tell… these are so many decorative shells we build around the pulsing heart of life endlessly begetting life. The 19th-century Swiss philologist J. J. Bachofen, in his study of gyneocracy in the ancient world, wrote:

The mother is earlier than the son. The feminine has priority, while masculine creativity only appears afterwards as a secondary phenomenon. Woman comes first, but man “becomes.” The prime datum is the earth, the basic maternal substance. Visible creation proceeds from her womb, and it is only then that the sexes are divided in two, only then does the masculine form come into being…

(T)he first earthly manifestation of masculine power takes the form of the son. From the son, we infer the father; the existence and nature of masculine power are only evidenced by the son. On this rests the subordination of the masculine principle to that of the mother. The man appears as creature… as effect, not cause. The reverse is true of the mother. She comes before the creature, appearing as cause, the prime giver of life, and not as an effect. She is not to be inferred from the creature, but is known in her own right. In a word, the woman first exists as a mother, and the man first exists as a son.

Serpent, Woman, Sea, and Moon

In an earlier installment of this series, I mentioned that a mythological motif calling up the image of Adam and Eve accepting the serpent’s gift can in fact be found in many Near Eastern cultures besides that of the Hebrews. There are late Sumerian and Akkadian seals, for example, that are variously arranged to present the same essential scene: either a serpent coiled around a tree full of fruit, or a serpent king/god in human form, with a serpent crown or some other identifier, handing out a gift, typically a fruit (or a goblet of the fruit’s juice or wine), to a male initiate, who is being directed to the serpent’s offer by a female attendant. Of course, we’re all familiar with the biblical tale of a woman leading a man to eat a piece of fruit at the behest of a serpent, but there is an important difference, which I’ll address later.

Serpents are often associated with the moon in world mythologies. There was a Native American tale in which the primordial Man forgot to attend a meeting at which the Creator would choose which of his creatures would live eternally. The serpent was present to accept the offer, and so acquired from the moon its power to shed its skin as the moon sheds its shadow to become new again. On the Sumerian seal pictures above, the cup being offered by the serpent king to the initiate has the symbol of the crescent moon above it. The association of serpent and moon, serpent and woman, woman and moon, appears again and again, with prehistoric roots that reach back to before the earliest river civilizations. This figure from c. 20,000-27,000 BC depicts a rotund female holding up a crescent bull horn (often used to symbolize the moon, for obvious reasons) with thirteen marks on it, while pointing to her pregnant belly with her other hand. There are thirteen lunar cycles in a year, and a human female ovulates about thirteen times in the same span, a fact which apparently was noticed as far back as the Paleolithic.

Cultures that share the serpent-woman-moon motif make it quite clear what these symbols mean to them. All three are symbols of material regeneration, representing the seething, pulsing powers of nature, of the endless birth and death of generations. Blood sacrifice, temple prostitutes, and other rites centered on sex and death predominated in the religious life of these societies. All three symbols, furthermore, are often associated with water. Serpents, with their smooth, liquid movements, are often found in water. The ancients who noticed the correlation between lunar and menstrual cycles would have also observed the relationship between the moon and the tides, and that a woman releases water immediately before she begins the sacred rite of giving birth.

The Mother Goddess was the supreme being of Bronze Age civilizations before they were conquered and wiped out by nomads from the Semitic desert and the Aryan steppe. The conquerors inhabited the cities and towns of their defeated foes, and their contact with the provincial village was minimal as long as their tax payments were consistently forthcoming. As a result, the new rulers were able to impose their own religion on the population centers, but shards of the older symbol system were preserved among the peasants scattered about the countryside. In her Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion, Jane Ellen Harrison makes the case that the mystery cults of the Mediterranean world were vestiges of the region’s pre-Homeric past. She described rites that were not performed in the shining Apollonian light of day, but at twilight or at dawn, and not in a mood of celebration, but one of foreboding. Offerings were made - always by women - in a spirit of riddance or pacification, to dark and indefinite deities that might be temporarily satisfied, but which remained dangerous, never to be brought under control or made subject to human designs. “The beings worshiped,” Harrison wrote, “were not rational, human, law-abiding gods, but vague, irrational, mainly malevolent spirit-things, ghosts and bogeys and the like.” Welcome to life in the Longhouse.

In one Orphic rite, offerings of sweet cakes were given to live serpents, and the reaction of the serpents to the offering was studied for signs of whether the coming year would bring good or evil. Sacrifices were not offered on sunlit hilltops, as with the Olympian cults of Classical Greece, but at first or last light in pits dug into the earth. It is important enough to reiterate that the offerings to the serpents were always made by women: as in the Mesopotamian seals and the Garden of Eden, it is Woman who is in direct contact with the serpent god. Just as Eve’s interaction with the serpent began the narrative of Biblical history, so did an eel come to Hina, the moon-maiden of Polynesia, to make her an offer that would begin their Creation story (the motif traveled well, even to islands with no snakes, where the eel served as an easy replacement).

Two common (though not quite universal) characteristics of Paleolithic and Neolithic art come to mind just now. The first is that images representing women are nearly always naked, while images of men are clothed, adorned, or costumed. Second, the two-dimensional paintings (when they represent humans) are typically of costumed men, while the three dimensional carvings are usually of women.

The meaning of the first point is obvious enough. The images of women, with ample breasts and hips – and occasionally holding out a breast or pointing to the belly or vulva, for viewers who require direct instruction – are nude because a woman, whose identity is rooted in the capacity to generate and nourish new life, has no need of outer vestments (that is, of culture) to tell her who she is. She carries her own meaning in her body. She requires no induction ceremonies or rites of passage, for her first menstruation is a more powerful initiation than a contrived ritual could ever be. Man, on the other hand, relies for his identity on the construction of symbolic social roles. He is pictured as costumed because he is nothing without a mask. Woman needs no language to articulate her purpose or fashion her identity; man cannot do without it. Woman’s destiny is rooted in her being, while man must fashion his own. Oswald Spengler wrote:

Endless Becoming is comprehended in the idea of Motherhood, Woman as Mother is Time and is Destiny. All symbols of Time and Distance are also symbols of maternity. Care is the root-feeling of future, and all care is motherly.

When the nomadic hunters and herders from the steppe and desert broke out against the Bronze Age goddess-worshiping agricultural civilizations, they brought with them their active, masculine warrior gods. These gods were not associated with the ever-revolving and ever-recurring cycles of life and time, nor were they vague representations of natural forces. They were conscious actors, heroes and seers in the image of man, battling it out for honor and supremacy. Rather than scratching out all memory of the earlier myths of the defeated people, the conquerors retained them - only they did so in an inverted form to commemorate their victory.

In the pre-biblical Mesopotamian representations described above, the liaison between the serpent lord and the woman at the foot of his fruit tree is not portrayed disapprovingly, as it is in the Bible. In the Bible, the serpent tells Eve that she will not die if she tries his fruit, but in fact will have her eyes opened and “become like God, knowing good and evil.” The Bible treats this as an elaborate trick by the serpent to bring down a curse upon all Creation, but in the pre-biblical versions the serpent’s words seem to be taken at face value - that is, it is not a trick, and he really is presenting the fruit as a gift.

In the mythology of the conquerors, the goddess and her titanic children were transformed into demons that had been overcome by their own heroic warrior gods. Thus, as noted earlier, at the beginning of time, Hebrew Yahweh slays Leviathan, Babylonian Marduk destroys Tiamat, Greek Zeus kills Typhon, and Indian Indra puts an end to Vritra. Out of the dragon’s corpse the new gods fashioned the world, which was not grown or given birth, but was built, like an artifact. The chthonic goddess, previously associated reverently with the serpent, was transformed into a terrifying dragon or a snake-haired Gorgon like Medusa, or, as we see in the Biblical version of Eve and her serpent friend, into the very source of evil and death in the world. This is our version of the story of civilization: the raw energy of nature is rationally arranged and made to conform to an order hatched by the human mind. The focus of life shifts from nature to culture - that is, away from the voluptuous nude female to the consciously contrived world of the symbolically costumed male.

And yet, in the examples of Medusa and the Indian goddess Kali, the myths of the conquering heroes carry a surprising ambivalence. Athena (a warrior goddess, born not from the loins of a woman, but from the forehead of her father Zeus) instructs Aesclypius how to draw blood from Medusa’s corpse, and how blood taken from her right side has the power to kill, while blood taken from her left side had the power to heal and resurrect. Or again, consider Kali, wife of the god Shiva (whose neck is adorned with a serpent), bringing death with one set of arms, but offering a gift with her other set.

Surprisingly, even the Bible is quite ambivalent on the question of serpents. After the incident with Eve, the serpent is cursed by God to go about on its belly, below all the other animals, and to be the eternal enemy of humankind. Yet a short time later, we find Moses wielding, of all things, a serpent staff which he uses to carry out his most famous miracles. Once, when the Israelites begin grumbling at Moses for having led them into the endless desert to die, God sends fiery serpents to bite and kill thousands of them.

Appealing to Moses, the people cried out, saying, “We have sinned, for we have spoken against the Lord and against you. Now pray unto the Lord, that he might take away the snakes from us.” So Moses prayed from the people.

The Lord said to Moses, “Fashion a snake and put it up on a pole; and it shall come to pass that every one who is bitten may look upon it, and live.” And Moses fashioned a snake of bronze and raised it on a pole. Then when anyone was bitten by a snake and looked at the bronze snake, they lived.6

That bronze serpent was preserved, and was for centuries an object of worship to the Hebrews until it was destroyed in the religious revolution of King Hezekiah of Jerusalem:

(Hezekiah) removed the high places, and smashed the idols, and cut down the sacred groves, and broke in pieces the bronze serpent that Moses had made: for unto those days the children of Israel did burn incense to it: and he called it Nehushtan.7

Later, in the Christian Gospel of John, Jesus alludes to his crucifixion when he connects himself to the bronze serpent of Moses:

“And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up: That whoever believes in him shall not perish, but have eternal life.”8

The narrative of the Bible, especially if the Old and New Testaments are taken together, can be read as the gradual development of the idea of the divine from the tribal war god we find in the Pentateuch into the more complex, much more expansive, even infinite, God that comes into view later. In fact, it’s worth noting that, in the chronological last two books of the Old Testament9, God neither appears nor speaks at all. The books are pure historical narratives, and God floats unseen in the background, glimpsed only in scraps of dialogue from humans who neither see nor hear of Him any longer. The Book of Job, in fact, marks the last time God speaks in the Hebrew Bible, which means that God’s speech to Job was God’s final word to man (if one is a Jew), or His final word before making an appearance among us in the flesh (if one is a Christian). The final exchange between the two must therefore be considered of utmost importance. And we’ll finally get to that next time.

I apologize for the scattered stream of consciousness, but I really do like writing about religion and mythology and sometimes I get carried away. Even now, I was about to launch into a comparison of hunter-gatherer and sedentary child-rearing practices, and how the differences might generate different personality structures and religious impulses among settled and nomadic peoples, but I could keep going with this stuff for 500 pages, and I realized that’s what was going to happen if I didn’t just cut myself off. But, if you’re interested in this kind of thing, I will write that post and continue with the theme off-and-on in the future. Thanks for reading!

Chimps make sounds to express feelings, to raise the alarm, to show off, etc, but they can’t tell each other what they plan to do tomorrow if it happens not to rain… only we can do that.

We’re told in the Book of Genesis that the Garden of Eden was located at the spot where the rivers Tigris and Euphrates originated, and both begin in the ancient homeland of the Armenians. Also, Mount Ararat - today located within the borders of Turkey, but historically an Armenian landmark - is supposed to have been the spot where Noah’s ark ran aground as the waters of the flood subsided.

It’s not inconceivable that it was the actual first word humans possessed. I can picture one of our half-ape ancestors trying to get the attention of his mate, and calling out “ma-ma-mamama” because it always gets her attention when the baby does it.

The Hebrew name for God in the Bible is YHWH (there were no vowels in the ancient Hebrew alphabet), which is variously translated as “I am,” or “I am who I am,” or, sometimes, “I am that which is.” The fuzziness of such an ancient translation indicates that our own language lacks a word that precisely corresponds to it. The closest English word for it is probably “Being.”

In later Vedantic philosophy, maya came to mean “illusion”, specifically, the illusion that reality is made up of distinct objects - as if a person believed that the ocean was made up of waves, foam, ripples, and currents, conceiving of them as actual “things,” rather than as epiphenomena of the vast, undifferentiated ocean.

Numbers 21:7-9

2 Kings 18:4

John 3:14

The books of Ezra and Nehemiah, which recount the repatriation of exiled Jews to Jerusalem by the Persians.

thanks Darryl, that was facinating. You must gave us a reading list.

Your meandering detours are a delight to read. I enjoy being along for the ride.