Hi everybody. Sorry this one took longer than usual to get out. About a week ago I babysat the festering buckets of disease my friend calls children, and was down for the count for a while. If it shows on the audio, I’m sorry about that, but I’m on the upswing, so have no fear for the future.

That’s right, all you FREE SUBSCRIBERS looking at this preview: Paid subscribers have access to a private podcast feed so that instead of reading, they get to listen to my sultry voice read it for them. Well, my voice is currently not so sultry, maybe I better think of a new sales pitch. How’s this: Martyr Made is a one-man show, entirely funded by you guys. I don’t have any sponsors, and I like it that way. I work for you, and nobody else. If you can spare $5 p/month or $50 p/year, you not only get access to this whole essay, but the audio version, and tons of other content as well. Oh, and you get a discount at the Martyr Made store, which is currently being updated with new products that will be online soon. So, if you can swing it, read an essay or two about slavery and help feed a hungry podcaster.

OK, here we go.

It’s time to talk about America. Finally. Well, it’s not America yet, it’s still just British colonies. Actually, it’s not even British colonies just yet. Let’s start in the mid-16th century. Spain is the dominant power in Europe. Her conquistadors have subdued the Aztec and Incan Empires, claiming vast territories stretching from modern-day Argentina to Florida and Southern California. By 1565, Spain had conquered the Philippines, which served as a base for trading expeditions shipping gold and silver mined in the New World to China, India, and soon, Japan, in exchange for tea, silk, spices, and other goods. Treasure-galleons streamed between Spain and her New World possessions each year, carrying gold and silver to Spain, and returning to the New World with more soldiers, priests, colonists, and supplies. The only other relevant player was Portugal, and by 1580 Spain and Portugal would be united under a single crown. The English, French, and Dutch overseas operations were limited to piracy and black market trade, mere parasites on the wealth flowing into the Iberian Peninsula. An observer at the time would have been justified in speculating that, in time, Spain might rule the entire world. Then again, the observer would have known that revolution, or rather, Reformation was in the air, and new challengers were rising.

Martin Luther’s protest went public in 1517, and within a short time the Protestant Reformation was sweeping the continent, reaching Switzerland (1522), the Netherlands (1530), Scandinavia (1531), England (1534), Scotland (1547), and generating violent controversy in France, a Catholic stronghold. Along the way, one sectarian split followed another, as Bibles were printed in vernacular languages and ordinary people felt empowered to interpret doctrine as they saw fit. The aristocratic territorial wars that defined the feudal era took on a new intensity as they morphed into existential religious conflicts.

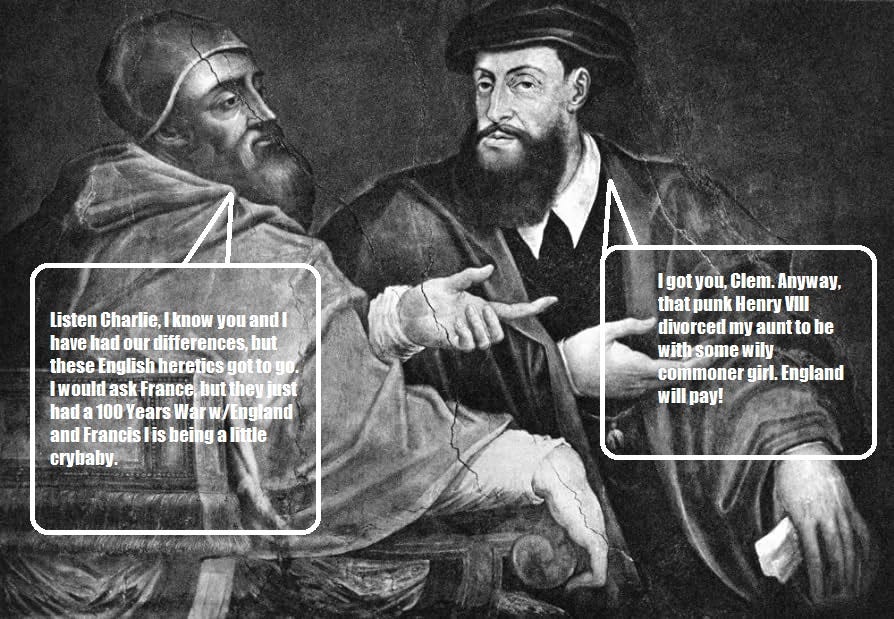

Charles V and Pope Clement VII were not always on the best of terms, to say the least, but as the ruler of the Holy Roman Empire as well as the most powerful Catholic nation, it fell to Charles to lead the Counter-Reformation, and stamp out the heresy tearing at the seams of the European order. The Church took some Protestant grievances seriously, and instituted reforms at the Council of Trent which drew many Protestants in Germany and France back into the fold. But other cases looked to the Church and the Holy Roman Empire to be pure opportunism and banditry.

For example, the English Reformation began when King Henry VIII grew tired of his wife, Catherine of Aragon, and petitioned for a divorce. Now, this was no mere request to annul a loveless marriage, it had geopolitical ramifications. Catherine was the prized daughter of the late King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I of Spain, honored aunt of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, and here she was being publicly humiliated by Henry because, of all things, he had become infatuated with the commoner Anne Boleyn. When the Church denied Henry’s petition for divorce, he decided to say screw the Church, divorced her anyway, married Anne, and just like that the Reformation was sweeping over England. Catherine was banished from court, and shuttled around a series of English castles, where she lived a life of prayer and fasting, usually confining herself to a single room except to attend Mass. In a letter to her nephew, Charles V, she wrote:

My tribulations are so great, my life so disturbed by the plans daily invented to further the King's wicked intention, the surprises which the King gives me, with certain persons of his council, are so mortal, and my treatment is what God knows, that it is enough to shorten ten lives, much more mine.

Even many of Henry’s allies thought his treatment of this noble and devout woman was a scandal. Poor Catherine died just a few years later. Although she had not given Henry a son, she did have a daughter named Mary. Catherine was not permitted to see Mary, but shortly before she died, she wrote to Charles V, King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor, with a final request that he protect her daughter, his cousin.

Not all Englishmen were happy about the sudden plunge into heresy, so Henry’s forces went to work convincing or eliminating them. Priests were killed, and, throughout England, monasteries and other Catholic property (which was considerable) was seized and looted. Before long, Henry, always impulsive but now increasingly unstable, had grown tired of (now Queen) Anne Boleyn as well, and had her beheaded on trumped up charges of adultery and incest. Henry would eventually run through six wives, and the unfortunate Anne Boleyn was not the last one he executed. So, as you can imagine, neither Emperor Charles V nor Pope Clement VII felt an obligation to treat England’s rebellion as an honest doctrinal dispute.

Henry only had one son, Edward VI (by his third wife, Jane Seymour, no relation to Dr. Quinn Medicine Woman… as far as I know). Edward took the throne when his father died in 1547, when the boy was just nine years old, but his reign didn’t last long. In 1553, when Edward was 15 years old, he fell ill and departed this vale of tears. With the accession of his sister, uber-Catholic Mary Tudor, as Queen of England and Ireland, the Counter-Reformation gained an important ally. Mary promptly married Charles V’s son, Phillip II, making Mary queen of Spain, but also making Phillip king of England and Ireland. Soon, leading Protestant churchmen were being thrown in prison, others fled into exile, and many (nearly 300) who refused to flee or be silent about their beliefs were being burned at the stake. The future history of Europe and, indeed, the world might have been very different if Mary had managed to produce an heir for Philip II, but she died at the young age of 42, five years into her reign, and was succeeded by her Protestant sister, Queen Elizabeth I.

Religious skirmishes were flaring up across the German states, and the French were having trouble with their own Hugeunots. Protestants in the Spanish Netherlands had chafed under Spanish rule for some time, and took the opportunity to launch a revolt of their own, beginning what would eventually be known as the Eighty Years’ War. All this is happening while Spain is colonizing half the New World, and trying to hold off Ottoman expansion in North Africa. So, as powerful as Spain is, she’s got her hands full at the moment.

All this is simply to say that the stakes of conflict were raised after the Protestant Reformation. For the Dutch and English ruling class, losing a war no longer meant simply bending the knee and paying tribute to the victor, but being deposed, possibly executed, and your kingdom being subjected to years of religious vengeance and inquisition. So, in the second half of the sixteenth century, after a century of watching from the sidelines, the English and the Dutch began to realize they’d better get themselves some colonies.